A few weeks ago Dorit Naaman and myself were interviewed on the Jerusalem Unplugged podcast, “the only podcast dedicated to Jerusalem, its history and its people.” It kicked off in late January and is hosted by Dr Roberto Mazza, an academic whose focus is the history of Ottoman Palestine. He is also the new editor of the Jerusalem Quarterly (which, however, is not related to the podcast).

Roberto opens every episode with the one question that is the same for every guest: What is your Jerusalem, what is your connection to the city? I’ve been a regular listener of his podcast since the beginning and so I anticipated the question. In the weeks leading up to our recording session, during my daily walks up and down the hills of San Francisco where I live, I pondered: What is my Jerusalem? I had never stopped to think about it before, to articulate it, even though Jerusalem has always been part of my life and the two main projects I work on these days are all about Jerusalem: this blog and the interactive documentary Jerusalem, We Are Here (JWRH) which was conceived and created by Dorit Naaman and in which I am both a participant and Associate Producer.

I’m not used to public speaking and I admit I was rather nervous, so I scribbled some notes in preparation for the interview. I have continued thinking about the question since. Here’s the extended answer:

What is my Jerusalem?

Jerusalem is the place my mother called home. It’s the place where she was born and where she spent her entire childhood.

Jerusalem is the place where my great-great-grandfather George Schtakleff, as a young man in his 20s, immigrated to from the Balkans in the mid-1800s. According to family lore, he first arrived as a pilgrim and figuring there were business opportunities there, he fetched his older brother Zacharias from Tetovo, a town in present-day Republic of Northern Macedonia (close to the Albanian border), and together they started a flour mill and bread-baking business. It’s the place where at least four generations of Schtakleffs built and lived their lives: they married, had children, went to school, worked and played.

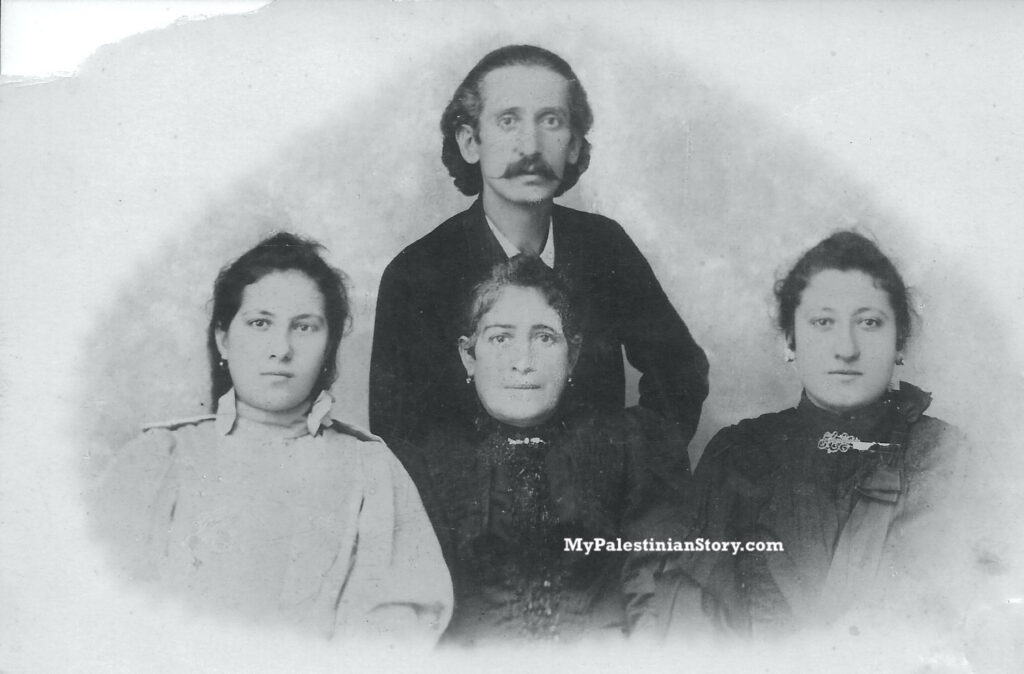

(plus an unknown woman, second from left)

Above his left shoulder, my great-grandfather John.

Jerusalem is also the place where my great-great-grandfather Anestis Agathopoulos, an Ottoman Greek from Asia Minor or Istanbul, found himself at the turn of the previous century, along with his small itinerant theatre troupe that consisted mainly of himself and his two daughters. In addition to being the director of the troupe, he was also the leading man to his eldest daughter Eugénie’s dramatic roles and the youngest Marika’s lighter, comedic roles.

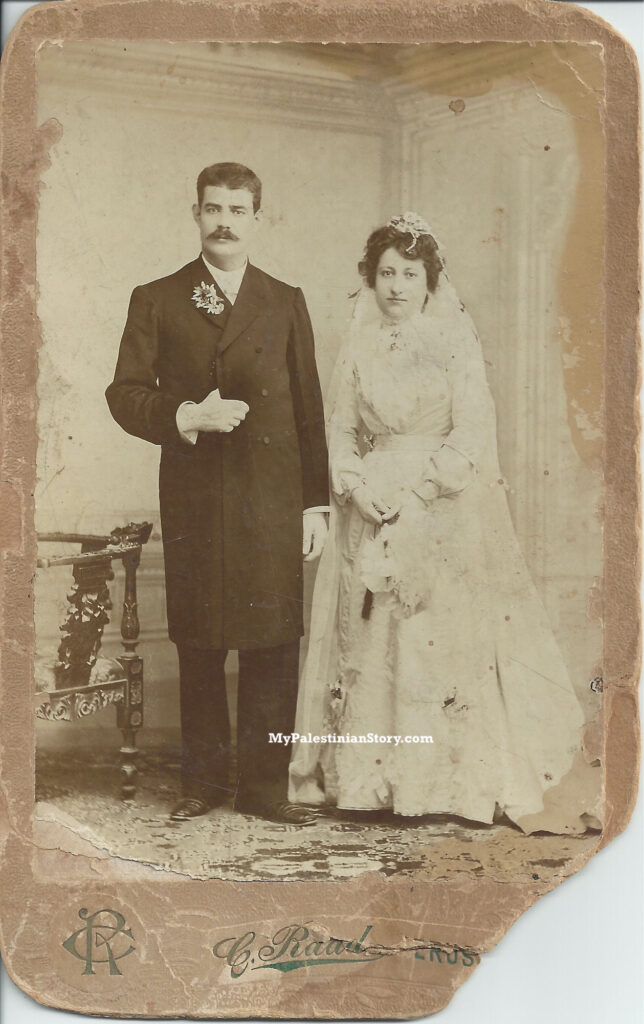

It was in some theatrical performance in Jerusalem (was it Shakespeare? Molière?) that George Schtakleff’s son John (Hanna in Arabic, Yiannis in Greek), eldest of six from George’s first wife, saw Eugénie on stage, fell for her and asked Anastasis for her hand. Anastasis promptly delivered his leading lady to miller John. They married in 1902 and with that, Eugénie’s career came to an end and the troupe disbanded.

My grandmother Paraskevi (Vitsa) was the couple’s first child, born in 1905 in Jerusalem which was still an Ottoman city. By the time the British arrived to occupy it in 1917, as the First World War was drawing to a close, my grandmother had four siblings and was receiving a French education in the school established by the nuns of the Notre Dame de Sion/Ecce Homo convent in the Old City. She was also becoming quite a proficient piano player who was often asked by her father to entertain his business guests. Her piano teacher wanted to marry her. But fate intervened.

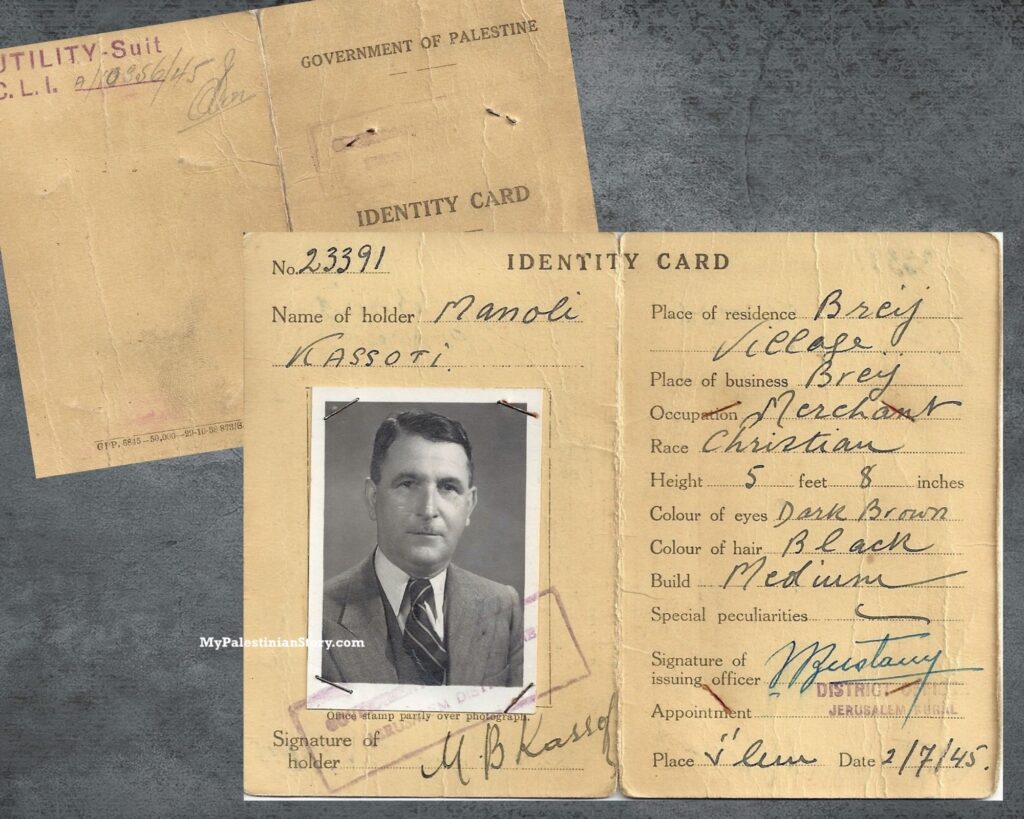

A young man from the Greek island of Samos was brought to Jerusalem to be raised by his uncle. His name was Emmanuel (Manolis) Kassotis and his uncle was the Greek Orthodox Patriarch of Jerusalem, Damianos I. Manolis grew up in the Greek monastery in the Old City and then his uncle sent him to university in Greece. Before finishing his studies and probably due to the outbreak of World War I, he returned to Jerusalem where he was assigned the lease of a huge estate, property of the Greek Orthodox Patriarchate, some 30 kilometres west of Jerusalem, by the village of Al-Bureij (aka Breij, or Brets in Greek). So Manolis became a farmer and estate manager. And somehow, somewhere, he met Vitsa and fell in love with her. His horrified mother, Kyrani, rushed from Samos to Jerusalem to put a stop to this marriage to—Lord have mercy!—a Bulgarian! A reaction somewhat unsurprising coming as it did in the wake of the Balkan wars (where Greece and Bulgaria had faced off). But Manolis would have none of it. Despite being a most pious Christian, he defied the stereotype of the Greek son and rather than give in to his mother he remained steadfast in his devotion to Vitsa.

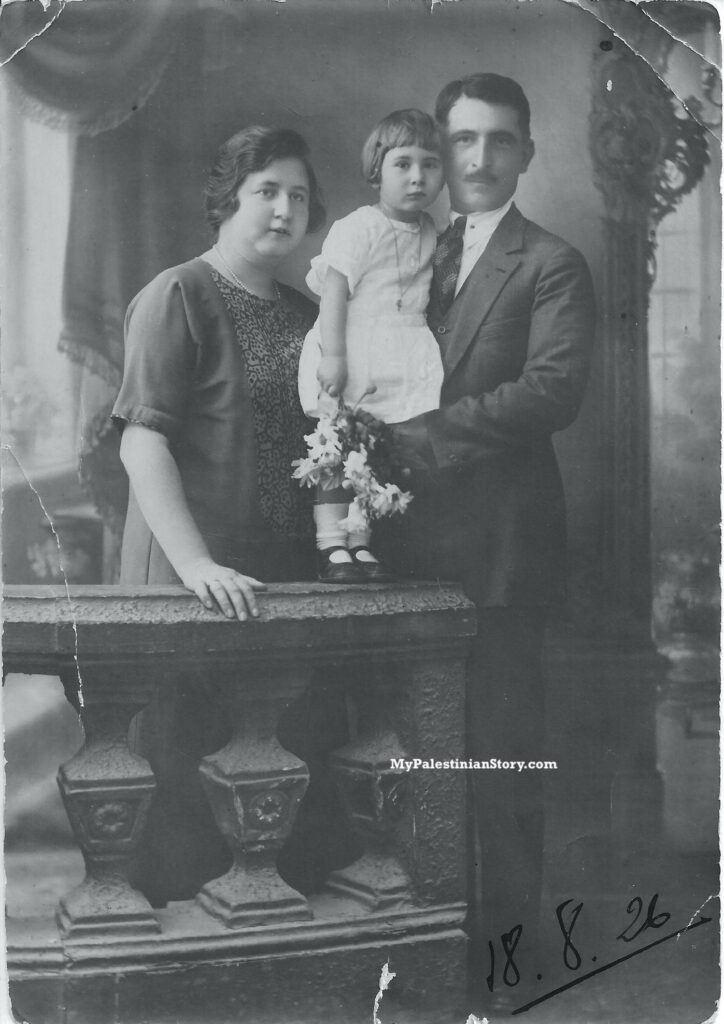

Manolis and Vitsa married in 1922 and my grandmother, only 17, left her cosmopolitan life in Jerusalem and her piano behind to become a farmer’s lonely wife. Kyrani, who lived with them in Breij (and died and was buried there) was instructed by her son to worship Vitsa daily!

Vitsa’s loneliness was alleviated by the arrival of their first-born, their daughter Vasso, in 1924, and also when Manolis finally bought her a piano. As the family grew, it became apparent that the countryside was no longer an optimum place to raise a family. To begin with, Vasso became a boarder at the German Schmidt College for Girls in Jerusalem. Then Manolis bought a house in Katamon and a few years after the 1930 birth of my mother, Anna, the family moved in. Breij continued to be part of their lives. My mother, Vasso, and various cousins and uncles had very fond memories of their times there. But Jerusalem was home.

Jerusalem was where my mother went to school (first at the Greek gymnasium in the Old City, then at the Jerusalem Girls’ College (JGC) for the benefit of an English education, and finally at the Arabic Al-Ummah when conditions in Jerusalem made accessing JGC dangerous); where the Greek community got together to celebrate national and religious holidays, to sing and dance at the Greek Club in the Greek Colony, or their community hall next to the church of St Simeon in Katamon; where various family members participated in sports and cultural activities in the YMCA; where Uncle Nando had his cinema, The Regent, in the German Colony; and where so many other memories and stories took place.

So Jerusalem was a place of convergence, the dot on the map where people from different places around the world, from diverse ethnic and cultural backgrounds, met and lived side-by-side or together, where they co-existed and intermingled. It’s the place where the seedling planted by George and Zacharias grew into a huge family tree with two large branches, each with a multitude of twigs that reached out and embraced neighbouring trees and encompassed many languages and cultures, spanning the gamut from Greek to Arabic to Russian, Bulgarian/Macedonian, English, French… I look at the surnames on the leaves and the diversity is mind-boggling: Schtakleff, Agathopoulos, Kircheff, Georgieff, Simich, Kassotis, Haddad, Tlil, Abdo, Illitch, Blajeva, Madjukoff, Gaitanopoulos, Kalandranis, Farraj, Barlas, Antippas, Thorogood, Samsonoff, Solodkoff, Katsinopoulos, Sfaelos, Galenoff, Lewis, Ladopoulos, Pittuck, Lachet, Siksek, Stellakis, Efthyvoulou, Hazboun, Sarouf, Cattan, Andary, Marcin, Fasheh… This is my tribe—that originated in Jerusalem!

But just before reaching its 90th birthday, the tree was violently uprooted as the city turned into the epicentre of dispersal. Jerusalem is the place all these people lost in 1948, along with their homes, their properties, their means of making a living, their community. All these colourful leaves were scattered by the winds of the Nakba—the Palestinian catastrophe—to the four corners of the earth. My family tried hard to hang on for a while but could not withstand the force of the winds of war. Today I have relatives, close and distant, in Canada, the US, Australia, the UK, France, Jordan, Lebanon, Greece and of course in Cyprus—and likely in more places that I have yet to discover.

And from that point on, Jerusalem became the place about which my family reminisced and told stories. Constantly. Every time they met. Jerusalem became part of the fabric of our family. There was some sorrow in the stories but also much joy: their lives in Jerusalem had been rich and full, and that’s what they wanted to remember. Their faces lit up when they talked about their hometown. The stories, despite always being underscored by nostalgia, had humour and laughter and adventures and celebrations and pride and mysteries and gossip… They drew me in like a magnet.

At first I would just listen—and couldn’t get enough. At some point I started making notes, asking questions, voice recording. At age 25 I orchestrated my first visit to Jerusalem with my mother in search of her house in Katamon. But I was still quite young and that visit was like a dream. I still couldn’t quite put the pieces together. But I’d had a first glimpse of the place, a first inkling of what it meant to my family, a first awakening to how it was lost to them.

When years later I got involved in the Jerusalem, We Are Here project and started my blog, my efforts became more methodical and systematic. I started learning history—real history as opposed to the family legends—and my curiosity grew. I realised that in many cases I had been too late to ask the right questions, as my grandparents and oldest uncles and aunts were already gone, brown leaves falling off the tree, returning to the earth where fragments of their stories are now buried forever.

The original Schtakleff never left Jerusalem. Great-Great-Grandfather George is still there, buried in the Greek Orthodox cemetery on Mount Zion where I found him for the first time in 2014 and where I visit him every time I’m there, to say hello, to prune the trees that all but cover his tomb and to assure him that I will continue to tell the story of what he started in Jerusalem. More of my ancestors are buried there, too, like great-grandmother Eugénie, but time hasn’t been so kind to them and their graves are gone…

My first visit as part of JWRH was in 2014. It was followed by several others. I started experiencing first-hand where the stories took place and getting a sense of what they were about. I met people who remembered my family, I found records and began to connect the pieces. And the memories, my family’s memories which I have inherited—they have essentially become my own—came face to face with reality and had to be reconciled against it. Memory is fickle and needs hooks in the real world to hang on to or it gets distorted beyond recognition.

which sprouted two floors and lots of walls – Jerusalem, 2014

My visit to the house with Dorit Naaman can be seen on the Yellow tour of JWRH (Kassotis)

From that point on, Jerusalem became like an old photograph that gets re-photographed: you shoot the same picture, the same frame, from the same angle. And then you partially superimpose the new on the old–like the photographs Tarek Bakri puts together.

The old, black-and-white part represents the abstract, the romantic, the faded memory and its emotional imprint; the new, the coloured version, is closer to reality: grittier, harsher, grounding.

That’s my Jerusalem: a collage of old and new, of memories and facts, of family stories and real history, along with the connections I’ve made and continue to make in the course of my explorations. ❖

Episode no. 18 of Jerusalem Unplugged with Dorit and myself was released on 26 May 2021. My thanks to Roberto Mazza for hosting us. To listen, click on the image below:

Lovely memories making history real.

Thank you very much!

I couldn’t stop reading. You are such a fantastic writer! The pieces of the family puzzle are all so neatly put in place as you tell the story. It was a nice journey to take from my hotel room in Newark at 1:00 am! Thanks for the journey.

Many thanks, Cous’!

Excellent story. Thank you for sharing Marina.

Thanks very much, Tasso!

Thank you for writing and sharing such a beautiful story in few words describing so many memories, emotions, frustrations that so many of us feel and experience.

Jerusalem! Jerusalem!

You are such a fabulous writer and so detailed.

Thank you cousin Marina ! You are blessed and do gifted to bring so many of us together.

Thank you, cousin Jennifer! Much appreciated

Thank you cous -I am with every word so much closer to our roots . Wonderful journey .

Thank YOU, Cous’! x

I’m only just beginning my journey into this rabbit warren of extended family and friends, all connected by the same thread, the cookie crumbs back to Jerusalem! I made my first visit there just over two weeks ago after losing my father John, and my head is still reeling. I’ve shed many tears in the past few weeks. I’ll be reading through all of Marina’s blogs here.

wonderful reading…came across you randomly…met dorit when she was here giving talks and went on a few tours. of course know anwar.. I live opposite mamelo (and anastas and stratis before anastas moved and stratis died…at 100? i used to watch stratis from my terrace carrying a bouquet of flowers each saturday to place on his wife’s grave in the Greek cemetery on Mt Zion)…. i note that cynthia and family lived a few doors down the road…their wonderful home is now being renovated. when you next visit, knock on my door at number 27 bethlehem road.

Many thanks for writing! Once again I’m reminded of how small the world is. I’ll most definitely take you up on your offer to knock on your door next time I’m in Jerusalem (hoping for next summer although the past year or so has taught me that long-term planning is futile…)

As for Cynthia, are you referring to Cynthia Schtakleff, Nando’s daughter? They lived on Emek Refaim. Did you have a connection with her?

Hi Susan, if only I’d read this before I visited Jerusalem in September. I visited Mamelo in the home where my father John grew up. I will definitely be going back!

you filled my eyes with tears-great memories

Thank you, John. I appreciate you writing!

Very interesting story! I have something to ask you. How can i contact you, Mrs Marina? Do you have an email address?

I’m glad you found it interesting. Thank you. You can contact me via the email on the contact page (or the contact form).