The last from last year’s trip, first posted on Facebook on 14 Jul 2014. Once again, lightly edited and with the addition of photographs.

Saturday was my last day in Jerusalem. And my last chance to visit the Greek Orthodox cemetery. I was glad I had gone exploring the afternoon before as I wouldn’t be wasting precious time now. So once again I walked across the old city, exited from Zion Gate and made straight for the cemetery. It was a hot day, the hottest one since my arrival, the official temp being 34C (93F). I was armed with a cap and water bottle.

of the Greek Orthodox cemetery

I was relieved to see the door was open (these are Greeks after all, wouldn’t put it past them to flout the opening hours.) An older man, small and bespectacled, was sitting behind a table in a covered space by the entrance. After a brief exchange in English, we switched to Greek. I told him I was looking for ancestors’ graves and asked him if there was a register of some sort, listing who was buried here. “There’s one in the office,” he said, the implication being: not here, not now.

Undaunted by the fact that I was potentially up against your typical Greek bureaucrat, I pulled out my iPad and showed him the photograph from 1974. “1974 was a loooong time ago,” he proclaimed discouragingly and explained that the Patriarchate had only wrestled control of the space from the State of Israel in 1976 or so, and before that the cemetery had sustained a lot of damage and no-one knew who might have been buried there earlier. Current records concerned only current occupancy, as it were. (Later in the day I was told that even the eyes from saints’ icons had been dug out by vandals.)

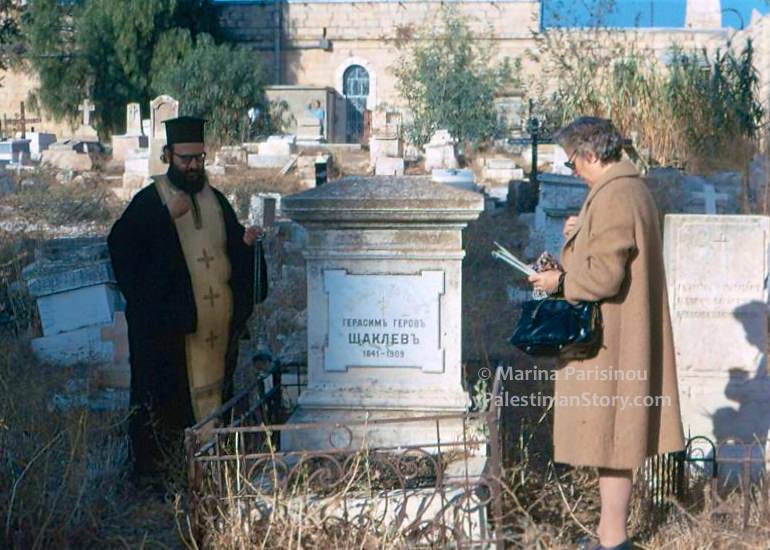

Photo taken by his son, Boris Schtakleff in 1974. Boris’ wife, Alexandra, on the right

But to my surprise, Photis—this is how he introduced himself—was game to try. He took his time examining the tomb on the photograph, then looked at the buildings behind it and asked me to follow him. “Bring that (the iPad) with you,” he urged.

On our way we bumped into an old Arab Orthodox priest. Photis suggested we ask him as he was very knowledgeable. He had never heard of or seen the name but assured me he’d pray for my ancestor and before I knew it he was pushing a cross onto my mouth to kiss. I shuddered at the thought of how many people’s germs I was picking up but the priest seemed so kind I didn’t have the heart (nor the chance, for that matter) to tell him I am a complete heathen. After repeated assurances of his prayers, he left Photis and me to our own devices.

The cemetery is of fair size and in a complete state of neglect. No pathways, weeds everywhere, broken tombstones scattered, some against the wall, others on the ground. It’s clear that it had been treated badly under the Jews and that many graves have been lost but I wondered how much care and effort had been put in by the Patriarchate to put things right after they took over. I’d wager on “close to none”.

We stood at a spot where we could see the building shown at the back of the photo. It was also an area with several Greek names around. We looked and looked but nothing stood out. This was a fairly bulky structure, it should have been easy to spot. Photis thought it very unlikely that the grave would still be here but to his credit he tried and kept asking to see the image again and in no time was using all the right gestures on the touch screen.

As we chatted, he explained that his real name is Munir as he’s an Arab Christian. Munir in Arabic means light, hence the Greek translation to Photis. He’s married to a Cypriot from Famagusta. Double trouble!

Seeing as we weren’t getting anywhere, and Munir/Photis needed to return to his post, I told him I’d take some time to meander amongst the tombs to see what I could find. I thought I’d be methodical and start at the furthest corner and just walk up and down but this was not an American city block, no grid system here. I clambered over broken tombstones, backtracked to get out of dead-ends and kept taking photos of any Greek names I saw. If I can’t find my own people, I figured, at least I could show my mum some familiar names.

Many inscriptions were in Arabic—quick elimination there—others in Russian or Romanian. The Russian, or rather Cyrillic, I had to look at as this is how the name appeared in the photo.

One section, slightly more orderly than the rest, seemed to be dedicated to clerics. I spent some time there because, despite my lack of religious beliefs, I’m “blue-blooded” church-wise: my maternal grandfather was a nephew of Patriarch Damianos which is why Papou Manolis came to Jerusalem in the first place. Before long I was rewarded with the name of Father Yermanos, a friend of the family whom I’d visited with my mum during our first trip here in 1986. Then his quarters were opposite the Patriarchate. He “moved” to this spot at the end of 1990, so not long after our meeting. I knew mum would be pleased to hear of him, to know something specific about his end.

The sun was beating down on me and the going was tough and disheartening. Inside me I kept urging Yiayia Eugenie to reveal herself but to no avail, she’s gone for good. Just as I was ready to give up, some familiar names showed up: Ignatiades, Arditzoglou, Vottarou, Demetriades, Mavromichalis… Some I’ve been hearing of since a long time ago, with others I’ve connected only recently. But it cheered me up and I photographed them all to share with my friends of corresponding surnames.

I realised that this would have to do. These names provided a link, if somewhat tenuous, to my mother’s Palestinian story and I felt that they would have to serve as my surrogate connection to this cemetery.

And then another familiar name popped up. One from… yesterday! Chamberlain! There were two names on the tomb: George Vrahipedis 1859-1922 and Antigone O U De Tankerville Chamberlaine, 1889-1978. The two family names on yesterday’s grave (see Part I) only I couldn’t figure out how they all tied together. Victoria Chamberlain married George Vrahipedis perhaps and they died within two years of each other. But what about Antigone, how did she fit in? Couldn’t figure it out. In fact, I still can’t. (If anyone has any ideas, let me know!) But it was exciting finding another piece of a puzzle.

I rejoined Munir in the shade and caught my breath. Then I pulled out the iPad again. I have been called obstinate or tenacious but I think of myself (rather more kindly) as… persistent. I re-examined the image and enlarged it further. Up on the right-hand corner I detected a corner of the back wall. Ergo the grave must be much closer to the side wall than we thought.

And then on the building at the back there was a door slightly to the left of the tomb. This was the wall I was leaning against. The overhead structure that now provided us with shade had been attached to it after 1974. I examined the real-life wall and realised it had only one door, the rest were windows. It was a makeshift, solid door, just a piece of metal with no ornamentation unlike the one in the photo but no matter: either way there was only one door.

I explained my logic to Munir who concurred. I entrusted him with my backpack and dashed to have one more look. iPad in hand I orientated myself based on the photo. Still nothing.

About to give up, I stood close to a large tree, tall, with thick foliage and low-hanging branches. Suddenly out of the corner of my eye, something grabbed my attention. Gotcha! It was great-great-grandfather George, quietly resting in the shade. A much bigger family tomb had been built on one side of the grave completely blocking its view and the rest of it was buried under the tree and other shrubbery. I was nothing short of elated. I’d found a Schtakleff in Jerusalem! And not just any Schtakleff. THE Schtakleff, the original Schtakleff, of four generations ago.

After Thursday’s visit to Katamon where I’d found my mother’s one-story house built up as a three-story apartment building—and in bad taste, to boot—with our friend’s (Mavromichalis’) house at the back converted to an ultra-nationalist synagogue and the whole neighbourhood changed irrevocably, dirty and untidy, I’d been dispirited and was about to leave Jerusalem with a heavy heart. My spirits now lifted.

I ran to fetch Munir who appeared to share my excitement. I don’t think he believed for a moment that I had any chance of finding the grave. But he wasted no time in switching to business mode. “Look at the stone”, he said. “It needs cleaning! And the iron fencing is so rusted! And all these weeds and foliage need to be removed and flowers planted!” Being a Middle-Eastern myself, I saw straight through this but cut to the chase. “How much,” I asked? “Oh, I’d have to bring workmen to do this… say, 100 Euro?” I said, “Look: I don’t mind the stone looking old, it is old (it’s probably one of the oldest graves in the cemetery) and the rusted iron doesn’t bother me and the flowers won’t last more than a few days. But I’ll give you €50 to clear away the weeds and cut the branches so the tomb can be visible and neat.”

I’m not naive, I realise he may never follow through but I felt I did right by my ancestors by at least trying. And I left Jerusalem that evening knowing that even though my mother’s house has been taken from us and altered beyond recognition, along with so many others of friends’ and family’s, there is at least one piece of land, as tiny as it may be, surrounded by iron fencing and with a stone structure inside it, that still has our name on it. We are still in Jerusalem. And come what may, a part of me will always be there. ❖

I followed the entire “ancestor chase” and enjoyed reading it – and glad that you found what you were looking for. I have done somewhat the same in other cemeteries – and the joy of finding what you are after is understood by likewise “sleuths” and “persistant” souls!

Thanks for the kind comments. V. glad you enjoyed the story. Hope to discover more in the days to come…

I read this page only which I came across by chance. Even if your family wanted to return to the house, they cannot because the state of Israel created a law to take control of the land and properties legally.

Moreover, the present Patriarch sold a lot of the land to an Israeli investor. Now it becomes twice harder to claim any property lost.

Thanks for reading!

Glad your quest was rewarding. I enjoyed reading about it.

Thank you! I’m glad you enjoyed it.