Before succumbing to the juggernaut of consumerism, the Christmas season was filled with the smells of baked goods wafting from home ovens. None evokes Christmas more vividly in my mind than the spicy, rich aroma of Yiayia Vitsa’s German Biscuits. (Biscuits in Brit speak, cookies in American lingo.)

Yiayiá in Greek means grandmother. Yiayia Vitsa, my maternal grandmother, was an amazing baker and cook who had made a name for herself in her adopted hometown of Nicosia, Cyprus. Her business activities were a means of supplementing the family income and eventually hers alone, as well as an outlet for her creativity. I’m quite certain, however, that Yiayia would never have imagined that this is what life had in store for her. In Jerusalem both her father’s family and the one she built afterwards with her husband were of comfortable means. How to conceive that they’d end up destitute in a foreign land?

Paraskevi (Vitsa) Schtakleff

Paraskevi Schtakleff was born in Jerusalem on 14 March 1905. Her father, John (Hanna) Schtakleff, was an ethnic Bulgarian/Macedonian whose father had emigrated to Palestine from the town of Tetovo in what today is the Republic of North Macedonia (not to be confused with the Tetovo of Bulgaria). Paraskevi’s mother, Eugenie Agathopoulou (Ευγενία Αγαθοπούλου), was a Greek from Istanbul (or Smyrna?). Eugenie’s father operated an itinerant theatre troupe in which he and his two daughters were the principal actors. Their travels took them to Jerusalem where great-grandfather John, upon seeing great-grandmother Eugenie perform, fell for her and hastened to ask her father for her hand which he was granted forthwith.

Eugenie bore him six children, the first being Paraskevi. The nickname Vitsa derives from the diminutive of her name: Paraskevitsa. She wasn’t fond of that nickname which gave her lots of trouble in childhood because in Greek it’s also a word meaning stick or whip. She impressed upon her three daughters that if they ever had daughters of their own, they could give them any name they wished except for hers. (As her only female grandchild, I’m particularly grateful for that act of humility and mercy!)

On the right, Marika (standing), Colias (seated) – Jerusalem, ca 1918

At the time of her birth, Jerusalem was part of the Ottoman Empire. The family was quite well off: Great-grandfather John ran a flour mill and bakery which supplied the Ottoman army with bread. Vitsa was raised in a comfortable home and went to school at the Notre Dame de Sion convent, receiving her education mostly in French. They spoke Greek at home and Arabic in the street.

Before reaching her teens, the Ottoman Empire collapsed and the fortunes of the family gradually followed suit as the British, the new overlords of Palestine, did not bring their business to John, possibly out of mistrust resulting from his close connection to the Ottomans.

In the meantime Vitsa had been taking piano lessons and had become quite accomplished. They had a piano at home where she was frequently called upon to entertain visitors. British visitors called her Freda. (Paraskevi is the Greek name for Friday.) Her piano teacher, a man by the name of Vamvoudakis, had wanted to marry her but Vitsa gave her heart instead to a Greek man who had emigrated from the island of Samos, probably around the time of her birth.

Emmanuel (Manolis) Kassotis was a nephew of the Greek Orthodox Patriarch of Jerusalem Damianos I who took him under his wing and brought him to Jerusalem when Manolis was about 12 years old. (More about my grandfather in a later post.) He subsequently took over the running of a vast estate that belonged to the Patriarchate, located some 30 km east of Jerusalem at the village of Al-Bureij (Breij). In Greek they called it Brets (Μπρετς).

Vitsa and Manolis’s marriage in July 1922 put an end to my grandmother’s modern city life. My grandfather was a stern and pious man and, although he loved my grandmother, he was also quite jealous. It’s not difficult to see how a man of the church would have a hard time reconciling with the lifestyle of a cosmopolitan young woman a dozen years his junior. So Vitsa’s sleeves and hems were lowered. Her new life in Breij was a far cry from the hustle and bustle of Jerusalem and she spent several lonely years there. Eventually my grandfather bought her a piano which was a great comfort to her, as was the arrival of the first of three daughters in 1924.

with eldest daughter, Vasso (aged 2) and Manolis – Palestine, 18 Aug 1926

I have been told that when my grandmother married, she didn’t know how to roast a chicken and my grandfather had to show her. Hardly surprising given her dedication to the piano. Was it in Breij that she learnt to make her delicious hummus and babaganoush, her tabbouleh and Palestinian lahmajoun (which looked very different from the Armenian version known in Cyprus)? Perhaps she was taught by the fellahahs who worked on the estate. I suspect keeping busy in the kitchen, in addition to being a requirement of her new role as married woman and mother, also provided some relief from loneliness. And perhaps having been initiated to the culinary arts, she expanded her repertoire to reflect her cultural background. Her scrumptious Soutzoukakia Smyrneika (Smyrna meatballs) (yes, I was a carnivore back in the day) must have come from her mother’s side of the family whereas the Tlatchen Piper (a Bulgarian pepper dip—which a cousin has recognised as a Macedonian dip by a different name) she was surely taught by her father’s Slav relatives.

When the first daughter reached schooling age, the family moved to Jerusalem where two more girls followed, the middle one being my mother. Breij remained my grandfather’s workplace and the family’s vacation getaway.

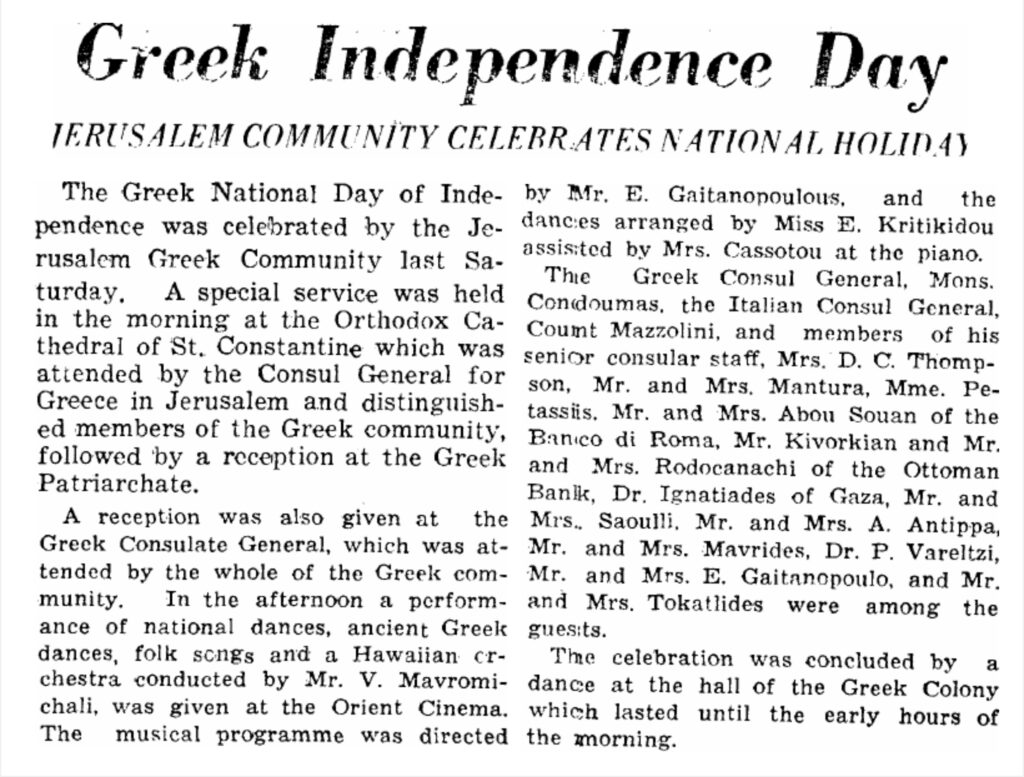

Life in Jerusalem was full. The girls went to school; Vitsa was a busy homemaker and also on the board of the Greek community’s charitable organisation. Like the rest of the large Greek community of Jerusalem, the Kassotis participated in Greek religious and national celebrations, and frequented the Greek Club in the Greek Colony where my grandmother’s hands were often found hopping around on the piano keyboard. On Sundays their lunch table frequently hosted guests and featured a roast chicken which Aunt Feely—Mum’s cousin and close friend—still drools thinking about.

The Palestine Post – 31 Mar 1939

With the partition of Palestine in May 1948 the family became refugees although at first they didn’t know it. They fled to Cyprus hoping to wait out the war so they could go back to their home and life in Jerusalem. But they were never allowed to return and found themselves destitute.

Baking for Family and Business

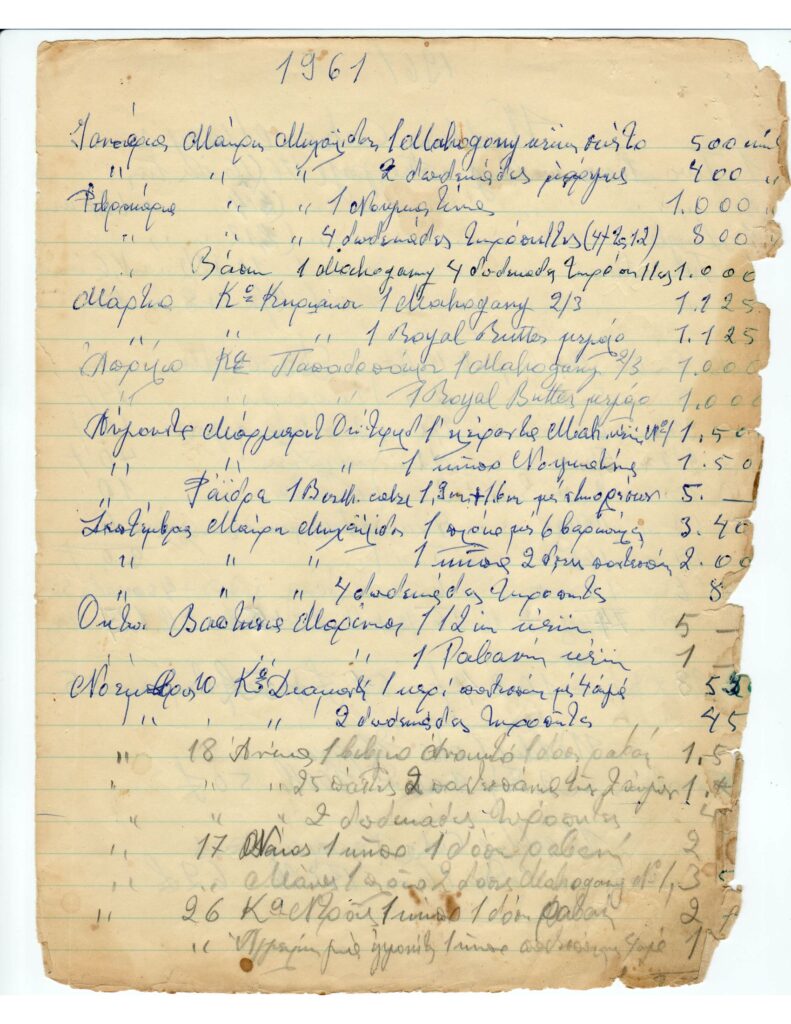

The main evidence I have for the beginning of Yiayia’s baking activities is based on her order books, the first of which is dated 1961. It’s a decrepit note book filled with a mishmash of recipes, cooking notes, cost calculations and orders, in a mishmash of Greek and English. In stark contrast with later years’ books in which each month’s orders filled a whole page and often spanned two or more, in 1961 all of her January-November orders took just one page, including two cakes for my October christening! A second page listed the Christmas cakes.

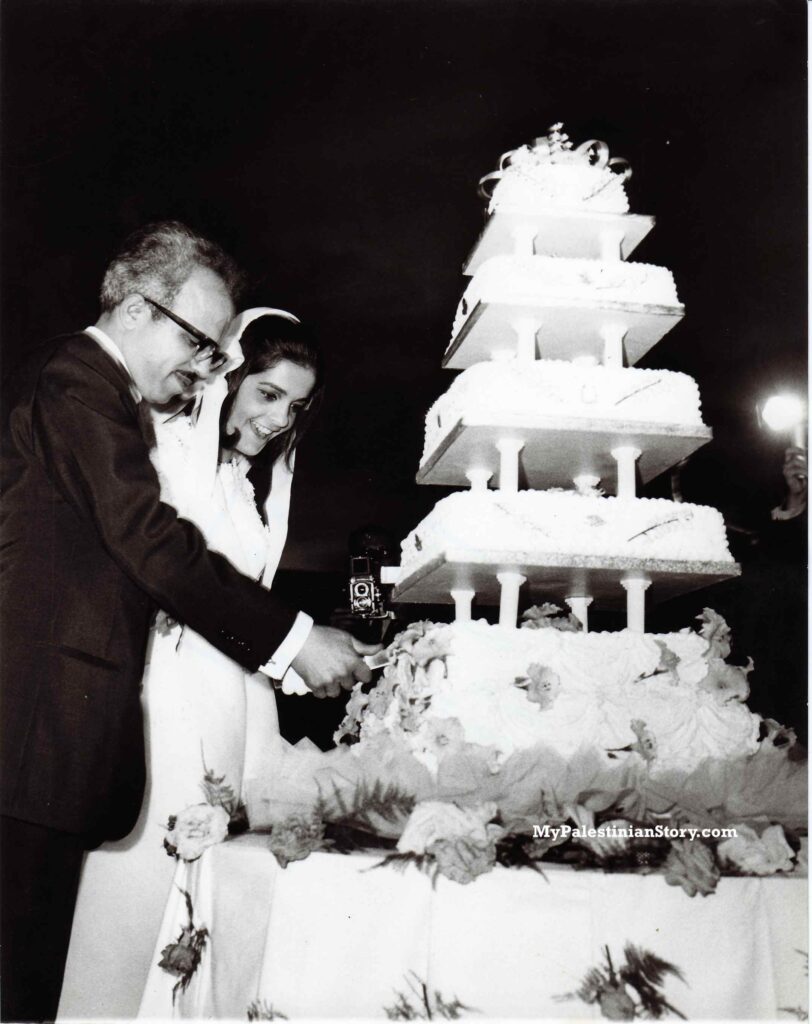

And then there were the wedding cakes for which she developed quite a reputation in Nicosia. She baked her first for her youngest daughter’s wedding: When Aunt Mary married journalist Alex Efthyvoulou in May 1961, the five-storey fruitcake covered in white hard icing was made by her mother. Two more wedding cakes followed that same year, both five storeyed, one weighing 100 lb (45+ kg), the second 140 lb (60.5 kg). These were the first “commercial” ones, priced at CY£50 and CY£62 respectively—not a trivial amount at the time.

By 1977 she had made 51 wedding cakes, ie around three a year. It was a major production which she used to stress over. Not only did it require intensive preparation and work, but she would also have to ensure that the whole construction could be safely transported. In some instances she would go to the venue herself to oversee the assembly of the floors. Some of the weddings (and cakes) made the newspapers. By late 1970s she started slowing down and only made a few more, the last one being in 1984 for Evi, eldest daughter of Ellie Savvides (née Louisidis), another Jerusalemite friend of the family.

On the right, the wedding of Minister of Interior & Defence Polykarpos Giorkadjis

and Photini Michaelidou – Jun 1967

Then there were the birthday cakes. So many birthday cakes! Dozens of Nicosia kids got a thrill on their birthdays from what my brother and I, as well as our cousins, took for granted every year: a custom-made cake. The process would begin with a visit to Yiayia’s flat where we’d thumb through the pages, sticky from all the dough Yiayia’s fingers had deposited on them, of dozens of magazines, many of them sent to her from the US by her brother Nando. Disney characters, fairy tales, trains, swimming pools, speed boats, rockets, and so many other designs would be transformed by Yiayia’s hands into cakes that looked amazing and tasted equally good.

Skateboard cake!

Cake decorating techniques have evolved a great deal since my grandmother’s time and some of her cakes may seem outdated. But Yiayia was a pioneer for her time and a master of sugar, frosting and the piping bag.

Her pièce de resistance was her swan. With the graceful bend of its neck and its angel-like wings, it was placed on a mirror which Yiayia decorated with sugar lilies. I had that for my sixteenth birthday but the swan’s beauty proved its undoing. We didn’t have the heart to cut it straight away, we thought we’d look at it for a few more days. And then for a few days more. And then one day we realised that the cake had gone bad.

The largest birthday cake Yiayia baked must have been the one ordered by the US Embassy for America’s bicentennial, which, if I remember correctly, had the map of America drawn on it.

Birthday Cakes Slideshow:

By far the most memorable cake was the one ordered by the wife of longtime mayor of Nicosia Lellos Demetriades. Lellos (as we all referred to him affectionately) had worked in partnership with Mustafa Akıncı, mayor of occupied north Nicosia, to build a unified sewerage system for the city. It was the beginning of what came to be known as the Nicosia Master Plan, a bicommunal plan for developing the two sides of the divided capital in a manner that would allow it to operate as one, should it ever be reunified. What Mrs Demetriades and Yiayia designed, based on a cartoon that appeared in the press, can safely be characterised as unique: the two mayors sitting across each other on… toilets, while at the edge of the cake were placed some… ahem… number-twos! (Not real ones, made of sugar of course!)

Lellos on the right, Akıncı on the left.

One of the many images that come to mind when I think of Yiayia is of her sitting in our living room during one of her regular visits, in her favourite armchair next to the fireplace, with her Slavic colours—fair skin, rosy cheeks, blue eyes—her long white hair braided like a halo around her head, and her long arthritic fingers tapping nervously as she pondered a structural issue for an upcoming creation. It could have been in one of those afternoons that she figured out how to turn an ice cream cone into a swan’s beak.

Then there were the everyday cakes—“Geography” (aka marble cake) and the like—and food for family, friends and many others. The names of the three Kassotou sisters appear in practically every month’s order list. In other words: we were the regular beneficiaries of Yiayia’s cooking and baking.

There were of course the expected seasonal ups and downs but, come Christmas, her kitchen and her hands went into overdrive. What came out of Yiayia’s oven was a reflection of who she was: a Greek-Palestinian whose adult years in her native land were lived under a British Mandate. Her Christmas repertoire included Greek melomakarona, Palestinian ma’amoul and English Christmas cakes. And, to break with the theme of origin and tradition, she also baked German Biscuits.

(Photos by Jules Parisinos)

German Biscuits

We don’t know how the German Biscuits sneaked into Yiayia’s cookery book. Most likely she came across the recipe in one of her many baking magazines. I also don’t know if she started making them in Jerusalem or Nicosia, although I suspect the latter. Regardless, Christmas in our family was not Christmas without them.

I missed them sorely after her death in 1992. A few years later I came to the conclusion that Christmas without Yiayia’s German Biscuits was no longer sustainable. So I baked a batch. I had made them once before, when I still lived in Cyprus and Yiayia was still very much alive to give me some pointers. I kept some and sent the rest home. The response I got from the family was nothing short of elation: it was as if I had given them Christmas back.

And so the tradition was passed on to me, Yiayia’s only granddaughter. The next year I baked more, the year after that even more. And just like my grandmother, I distributed them to the family. I would also give them to friends both here in the US and in Cyprus in lieu of purchased gifts and they loved them and came to expect them every year. And they were not shy to voice their displeasure if I missed a year. The packages I dispatched—express, of course—from San Francisco to Cyprus, London and the East Coast ran to at least a few hundred dollars at the post office.

For several years, Pat, a good friend from work, was my most able assistant and egg-washer par excellence, and as such became part of the tradition. We baked together for several years until she moved to Atlanta—and even one year after that, when she came back to San Francisco especially. Other friends also became gracious volunteers at times. The last time we baked with Pat, the dough was over 20 kg (about 46 lb) producing 830 biscuits.

As I would recover from this exhausting—for me—feat, I would reflect in amazement on Yiayia’s own output. Not only did she produce more biscuits than I, but they were only one amongst a whole array of other Christmas goodies, in equally impressive quantities. One little old lady who walked with a cane, in her home kitchen! And there was me, fit in my 30s and 40s, utterly knocked out by a mere 20 kg of dough!

Inevitably the recipe has evolved in my hands over the years. Shopping for the ingredients that first time presented some minor challenges. I remember asking at my local supermarket in Berkeley, CA, for “mixed peel” and drawing blank looks. Luckily I spotted a package myself and learnt that in the US it’s referred to as “candied fruit”. One glance at the ingredients list, full of preservatives and colourings, is all it took for me to come to terms with the fact that the recipe would have to be adjusted. Our knowledge of nutrition has come a long way since Yiayia’s days and the biscuits would have to keep up with the times.

So I substituted dried fruit (organic, of course) for the mixed peel. And out went the Spry shortening (with its trans fat), in came the butter (having been restored to the world’s good graces). The flour I used was mixed 50%-50% white and wholemeal from the beginning. Then I discovered Whole White Wheat flour—flour from a white berry with its wholemeal texture being very close to the refined flour from the more customary red wheatberries—and thus the biscuits became 100% wholemeal. In later years I even made a couple of batches with canola oil rather than butter when I got word that a cousin in London was on a vegan diet for medical reasons. What remains unchanged, however, is the sliver of blanched almond placed in the centre of each biscuit, like a heart. Yiayia wouldn’t have it any other way!

German friends have identified the biscuits as (at least akin to) the traditional Lebkuchen found in German Christmas markets. Most everyone thinks they are ginger biscuits although there is no ginger in them. There’s cloves and cinnamon, citrus zest, and almonds and honey… (No, sorry, the recipe is not available to the public! The three Kassotou sisters have stipulated that it remain strictly in the family, at least while they’re still on this earth. Two of them are sadly gone but thankfully the youngest—and strictest about this rule!—is still with us so I’m keeping this recipe card close to my chest for now and hopefully for a while still.)

I have not abandoned the tradition—at least not in theory. In practice I haven’t baked for several years now, what with one thing and another. Even though I contemplated the possibility, it wasn’t meant to be this year either. Next year, inshallah!

But the holidays are here and I’ve missed the German Biscuits and I’m sorry I haven’t been able to share them with family and friends so we can remember my beloved grandmother. What I can do though is honour Yiayia Vitsa and her baking through this post—with much love.

PS – When the pandemic started with its lockdowns, I began going through the material I have on Yiayia Vitsa—her order books, diaries, etc—thinking I’d write a book about her and her kitchen. But then the Semiramis book took precedence. In drafting this post, I realised how much more there is to share about Yiayia so a book about her has to happen at some point. ❖

wonderful! I remember baking w/you one year! we had a great result!

Thanks for the reminder and memories! Stay well! hope to see you soon!

Thank you, Chère. Yes, you were one my gracious volunteers!

Dearest cousin Marina- I hung onto your every word . This is truly priceless as I am mesmerized by Thea Vitsa’s talent and her story. Yes, please do write the book- your post has me wanting more!

Ever so grateful for you sharing these treasures! Thank you . And next time you bake the biscuits, please send a care package to Montréal : ))))

Many thanks for reading and your sweet words, Corinna! I’m glad Yiayia’s story touched you. With a little bit of luck, there’ll be a package coming your way next holiday season! 😉

What a great memory of your grandmother. Baking is a unique talent, nothing to do with cooking.

Thank you, Vicky!

Thanks for sharing your memories, My mother also used to bake German cakes and cookies, I imagine she learned that at Schnellar.

Thank you for reading! Another person mentioned the German cookies from Schneller so I’m beginning to suspect that that’s where my grandmother discovered them.