This post is dedicated to the memory of my uncle Yiannaki (John/Jean) Schtakleff who left this earth too early—in March 2018, aged 74.

Each family has its story, what they tell each other and their children about the past, about their ancestors and their experiences: the whences and thences, wherefores and hences. Most family stories are in essence legends and lores which almost always diverge, to a lesser or greater extent, from reality, from history, from what actually really happened.

My own family story, particularly that of the Palestinian side, ie my mother’s, captivated me from a very young age. At some point, the standard tales, which we all repeated in the family, no longer satisfied me: I wanted to know more. It’s then that I realised that your family story which seems to run like a simple, straight line is in fact a web—with you caught in the middle! You look at what’s on this line and at some point you start tossing things around in your brain and suddenly the brain is inundated with a bunch of question marks that seem to dart off in different directions. But, but… why did he do that? Where did he come from? When? Why? But how come he… and she… and yet…. ??? You start chasing these question marks and they lead to more and more, and before you know it, you find yourself far from the original story which by now doesn’t hold water entirely and appears to be much more complex, with an increasing number of unknowns. When you add some historical information to the mix, the story begins to acquire texture and dimension even if it loses a bit of its lustre. It becomes more real and yet every now and then you still discover some moments of magic.

Such has been my experience over the years. Let’s take for example the story of what happened to two of my grandmother’s siblings in the Nakba, the 1948 catastrophe, when the creation of the Jewish state caused Palestinians to flee Jerusalem.

My grandmother, Vitsa, was the eldest of five and one of two girls. In 1948 she was married and had three daughters, the middle one being my mother (aged 18). In late April 1948, they fled Katamon in the nick of time, just a day or two before the big battle that took place there, and after some hairy adventures (to be recounted in a future blog post) arrived in Cyprus. Hence me being a Cypriot. Her sister, Marika, with her husband, Efthymios Gaitanopoulos, and their two daughters, Feely and Jenny, had left for Egypt earlier, soon after the bombing of the Semiramis.

Of the three brothers, Colia, the youngest, had already gone to the States where he’d hoped to pursue a career in acting. And that leaves us with the two brothers: Nando and Coca. Nando was married to Efi, had two children—Cynthia and Alex (the latter being mum’s youngest cousin)—and ran the Regent Cinema. Coca, with his wife, Athena, had one son, John (or Jean or Yiannaki in Greek—second youngest cousin), and was making electrical repairs in a shop Nando had round the corner from the Regent.

The story goes that Nando and Coca joined a large convoy of Palestinians that were fleeing to Egypt where upon arrival they were refused entry and were instead kept in a detention centre for an unspecified length of time. The detention centre I later discovered was in Kantara (El-Qantara) a town in the middle of the desert, on the Suez canal, roughly half-way between Port Said and the Great Bitter Lake. An old British army camp, it had played an important role in the defence of the Suez against Turkish attacks in WWI. It also marked the starting point of a new railway east, towards Sinai and Palestine, begun in 1916. It developed into a major base and hospital centre with an adjacent cemetery. In WWII it was again a hospital centre. The cemetery evolved into the Kantara War Memorial Cemetery which today contains 1,562 Commonwealth burials of the WWI and 110 from WWII. In 1948 hundreds of Palestinians gathered there and were housed in prefab buildings, among them familiar names like the Antipas and the family of Renée, my mother’s dear childhood friend.

At some, unspecified again, point in time Nando & fam returned to Jerusalem. This time it was to the Jordanian-controlled Old City, as their home was no longer accessible being as it was in the area occupied by the state of Israel (what came to be known as West Jerusalem). Eventually, in the early 1950s, they made their way to the US. As for Coca & fam, somehow they found themselves in Beirut where they stayed until 1975 when troubles erupted there as well and then they, too, ended up in the US.

Colia, whom I had interviewed extensively in 2003, had told me that somehow Nando eventually made it to Cairo, and that was because, unlike Coca, he was financially a bit more comfortable, the implication being that you needed money to be allowed out of Kantara. Even so, they only stayed in Cairo for a very short period of time.

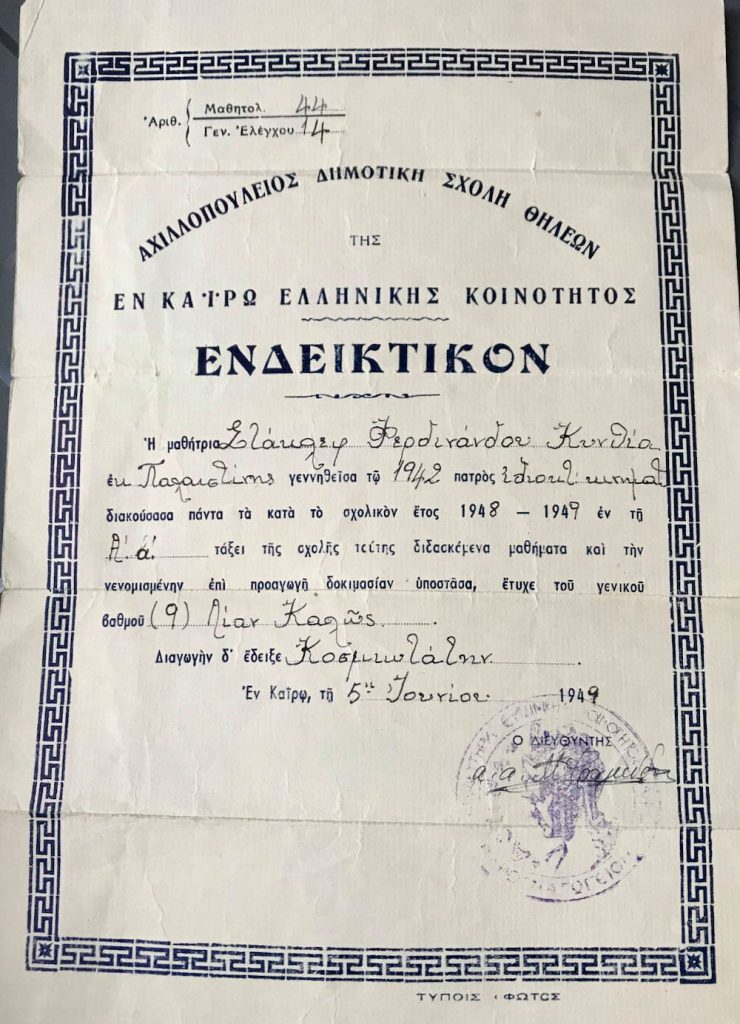

New light was shed on this recently when Alex and his wife, Joy, went rummaging through Nando’s papers in New York and sent me a few treasures. One of them was an end-of-year Certificate from the prestigious Achelopoulios Greek Primary School in Cairo (Αχιλλοπούλειος Σχολή Καΐρου). In June 1949 Cynthia graduated from the first year with a grade of 9/10 and excellent behaviour. So they had spent that entire first year in Cairo. By that time the 1949 Armistice Agreements between Israel and its Arab neighbours had been signed so Nando must have realised that a) there was no going back to their home and b) it was probably safe enough to return at least to the Old City of Jerusalem.

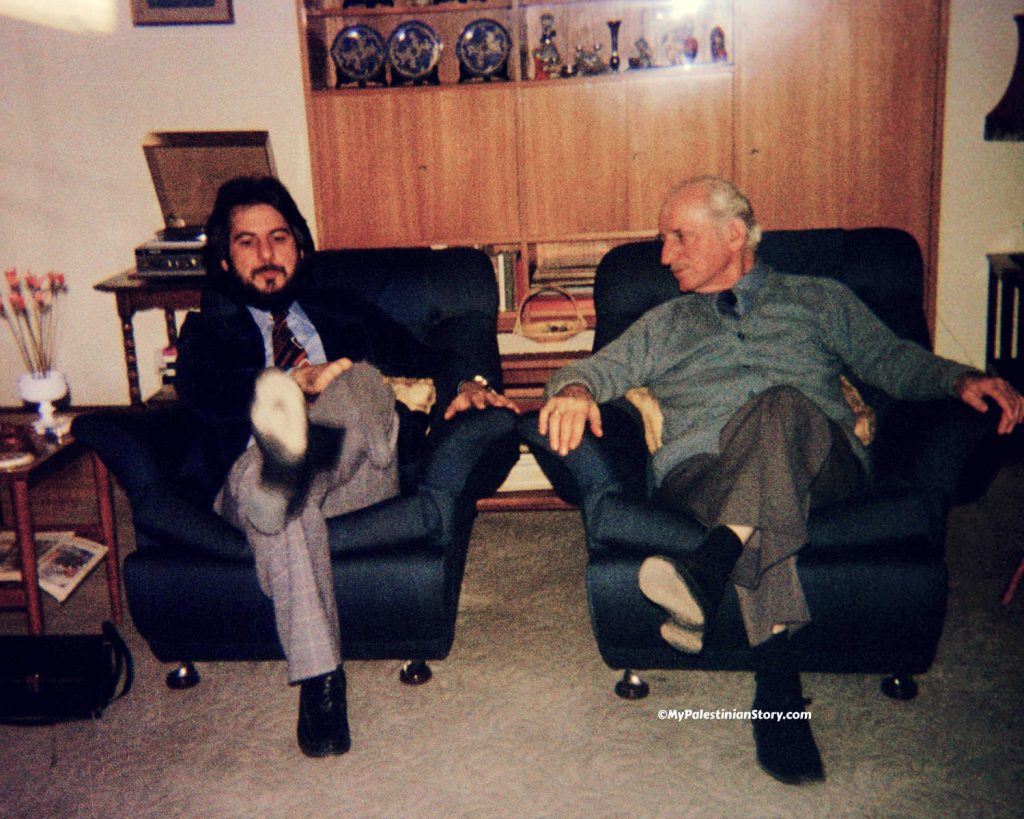

But Coca’s story remained obscure. That is, until this past holiday season when I resumed transcribing the hours and hours of my interviews with family members. In October 2006, I spent an hour with Yiannaki and his wife, Liz, in their home in London, talking family history. We reviewed the family tree and Yiannaki talked about their story.

It turns out that Coca also made it to Cairo. I don’t know the circumstances, ie how they managed to leave Kantara, but they in fact stayed in Cairo much longer than Nando. This was news to me (and also brought home how feeble my memory is and consequently the necessity of putting all this down in writing).

This is the story Yiannaki told me:

Upon arrival in Cairo they connected with Coca’s cousins, Lisa and Olga, who introduced Coca to their uncle Sanco (Alexander). Sanco was one of his father’s brothers who along with three of their sisters had been kidnapped, as children, by the Catholics in Jerusalem and taken to Egypt. Two of the girls became nuns, the third left the church eventually, and the brother, Sanco, joined the Christian Brothers. (Talk about family legends! If I ever get to the bottom of this one, I’ll be very pleased indeed.)

The Institute of the Brothers of the Christian Schools (aka Christian Brothers, De La Salle Brothers, Frères des Écoles Chrétiennes) was founded by Jean-Baptiste de La Salle (1651-1719) in France and is now based in Rome. In fact the three Schtakleff brothers—Coca, Nando and Colia—had attended the Collège des Frères in Jerusalem, too.

Sanco offered to help his nephew Coca who was practically destitute, having lost his Jerusalem home and living. He promised to take care of Yiannaki’s education and have him attend the De La Salle schools. Athena, knowing the story of the kidnapping, freaked out and had visions of her son also being kidnapped, taken to Rome and turned into a priest. However, Sanco reassured them that times had changed and what had happened to him—which he seemed to regret—could no longer happen. Sure enough, Yiannaki attended the Collège des Frères in Bab El Louk throughout their stay in Cairo and when they moved to Beirut in 1956-57, he continued his studies at the De La Salle school there, until graduation.

Nearly three decades later, Yiannaki returned to Cairo for the first time. It was in the early 1980s, perhaps 1984, and he was on business with a colleague from California, called Dave. On their day off, he told Dave that he was planning on tracing back history and he invited him to follow. Dave took up the offer and tagged along.

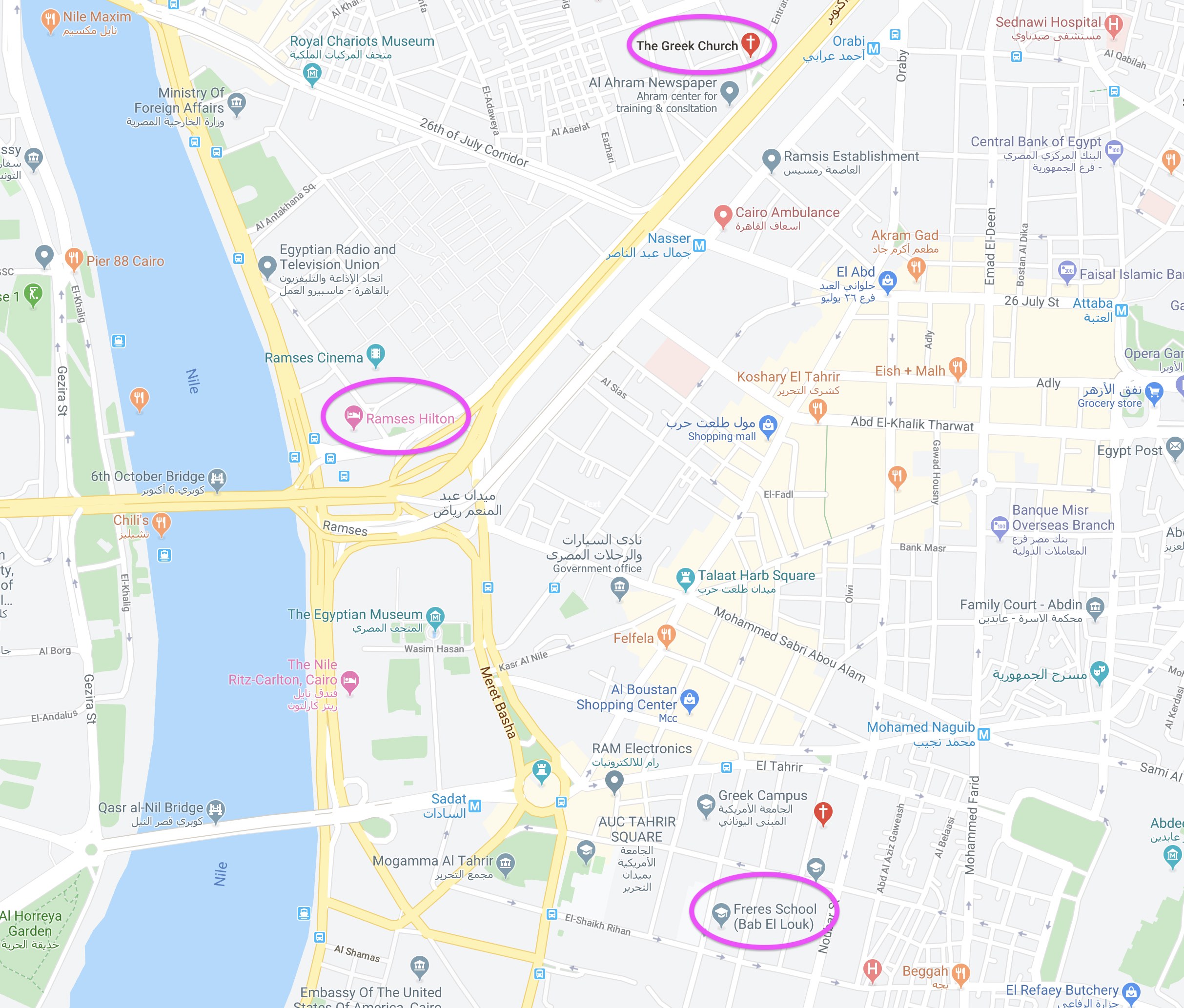

First Yiannaki wanted to find his school. They were staying at the Intercontinental Semiramis Hotel on the Nile. The school was not far, a 15-minute walk towards the American University of Cairo. There was the AUC, then the French Lycée of Cairo (which I’m guessing is today’s Lycée El Hourriya) and then the Collège des Frères Bab El Louk, next to the train station that goes to Maadi.

Yiannaki was feeling very emotional: it had been so long. They first walked through the playground where he felt that time had stood still. Then they entered the building. They walked past a class in session and Yiannaki, stealing a glance, recognised the old teacher. He then requested to see the headmaster and was told to wait as he was due back in 15 minutes. So they sat on a bench in the playground and watched the kids play basketball, Yiannaki overcome with memories. As they sat there, they saw an old bus pull in. Yiannaki stared at it and then turned to Dave: “I’m pretty sure this is the same bus that used to take me home.” Dave looked at him in disbelief, thinking perhaps that his friend’s emotions were in overdrive.

Eventually the headmaster returned, in a little Egyptian Fiat. Driving in he noticed these two strange men. Yiannaki was in a white suit, his dark hair was long and he sported a long beard. They walked up to each other and introduced themselves. Yiannaki told him that not only had he been a student at the school so many years ago but also that Frère (Brother) Evagre was his uncle. That was the name that Sanco had taken on as a Christian Brother.

So he enquired about Frère Evagre and the headmaster said he had known him (he had since died). In fact a student of his, another Brother, was still at the school, so he summoned him. Before long an old man came to join them and the headmaster made the introductions, explaining Yiannaki’s Frère Evagre connection. The guy looked at Yiannaki and without a single word turned around and walked away. The headmaster made apologies for him. Apparently Frère Evagre had become quite famous back in his day, writing literary books in Modern Arabic (as opposed to old Arabic which had been the norm till then) and had been quite prolific. When he died, some of the teachers “stole” his books and so this man must have thought that Yiannaki was there to steal his teacher’s collection. On hearing this, Yiannaki asked if he could indeed have just one book, for the family. Seeing the old Brother’s reaction the headmaster didn’t think it would be a great idea. “Today it would be difficult, come back another time.” By the time Yiannaki returned to Cairo, the headmaster was no longer there and the story had been forgotten.

(I have heard stories about Sanco before, that he was called Frère Evagre and had gained fame in the Christian Brothers, attaining the title of “Inspecteur”. However, I have been unable to find anything online so far, as there were a couple of Frères Evagre before him, much better known than our ancestor. One of them in fact was instrumental in founding the Frères schools.)

Then there’s the story about the school bus. Yiannaki asked the headmaster if the bus was the same Dodge that had shuttled him back and forth in his student days. He even remembered the name of the driver: Ramadan. The headmaster called the driver over. The old man shuffled along and, lo and behold, it was the same driver! When he approached, he looked at Yiannaki and said in Arabic: “Hey, Schtakleff, what are you doing here?” He had recognised him! Yiannaki threw his arms around Ramadan engulfing him in a big hug. Dave was in tears.

The house where they had lived was in the Pilavakis building (Cypriot-owned). It was now “cut in half” and was right behind the new Ramses Hilton. Not far from it was one more place Yiannaki wanted to visit: the Greek Orthodox Church of Saints Constantine and Helen. The church had been a big part of his life in Cairo. Not only did he go there regularly with his parents but he was also a boy scout. And the priest, Father Ioakim, was from Palestine and knew Coca and Athena well.

So they made their way to the church which had been a beautiful cathedral in their time and found it dilapidated. (It has recently been inaugurated to much fanfare after two years of extensive restoration work.) An Egyptian guard was sitting outside. Yiannaki asked if the church was open; it was. He asked if Father Ioakim was still there and the guard said he was inside. A christening had just taken place and people were streaming out of the church.

Inside, the church looked just like before but quite run down. Someone was singing in the sanctuary. Yiannaki remembered Father Ioakim’s melodious voice. The old floors creaked under their steps. Ioakim who was in the process of removing his vestments looked up and saw these two men approaching gingerly. He deposited his vestments in the sanctuary, came out again, and stood in front of the iconostasis, a few steps up from the church floor. Yiannaki looked up and addressed him by his name. Father Ioakim responded: “Yiannaki!” Once again, Yiannaki was astounded at being recognised after so many years. He asked Father Ioakim the same question he asked Ramadan: “How on earth did you recognise me?” Twenty-six or so years older, with a beard, long hair… Both gave the same answer: “From the smile in your eyes!”

I remember those smiling eyes fondly. Rest in peace, Yiannaki.

Yiannaki’s story reminded me of a couple of surprise encounters my mother and I had when we visited Jerusalem together in 1986 which I’ll recount in the next post. Stay tuned for Part 2. ❖

You write beautifully dear Marina! I relish every word and look forward to more…

Greatly appreciated, Mary!

Thank you, dear Marina, for this beautiful tribute to your uncle Yiannaki. You did phenomenal research for this piece and you wrote it with so much love. Thank you for being your family historian!

Many thanks, Mona!

How wonderful to ‘read’ you again ! you write so beautifully, please don’t stop , your writings are such a treat ! I have missed you, any chance of a visit to the Holy Land ? Meanwhile take care and thank you for the pleasure.

Thank you, Marianne! Much appreciated. Perhaps I can visit again over the summer. Let’s see how things go. Would love to spend more time with you.

What a beautifully written account of your family’s history. These stories are precious; thank you for sharing yours.

Many thanks, Sato! Coming from you it’s particularly appreciated.

Dear Marina,

Quite by accident I started reading your piece, and join all the others who comment about how well you write. You make every bit so personal, and so universal and so moving…do continue to write. I know how much work is involved in collecting and gathering the little bits of information into a coherent story. You did it!!

Lovely to hear from you again, Leorah. Many thanks for your kind words. I appreciate the encouragement!