~ The story of my grandfather Manolis Kassotis—Part 2/2 ~

(The story continues from Part 1: An Unrecorded Death)

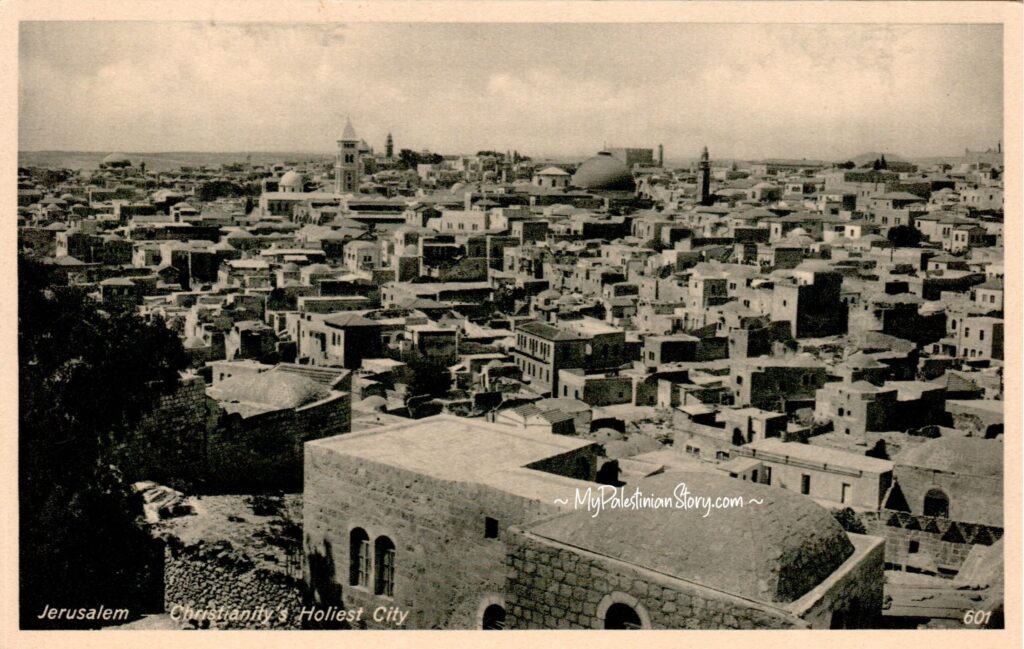

Last Days in Jerusalem

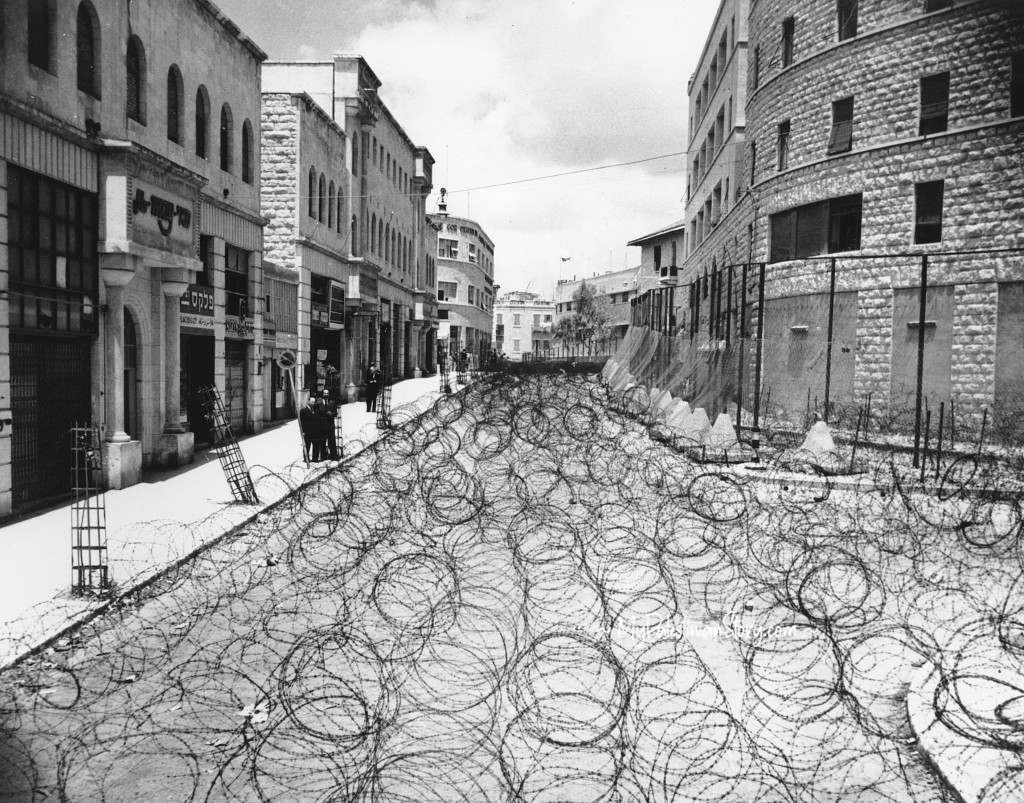

The clouds of war that had been gathering over the land for years became darker and more ominous after the conclusion of World War II. When, on 29 November 1947, the United Nations voted to partition Palestine, the tempest was unleashed. Explosions, snipers, barbed wire—physical manifestations of fear and hate—became everyday fare in the life of Jerusalem.

(AP Photo, Ref #: PA.8650556)

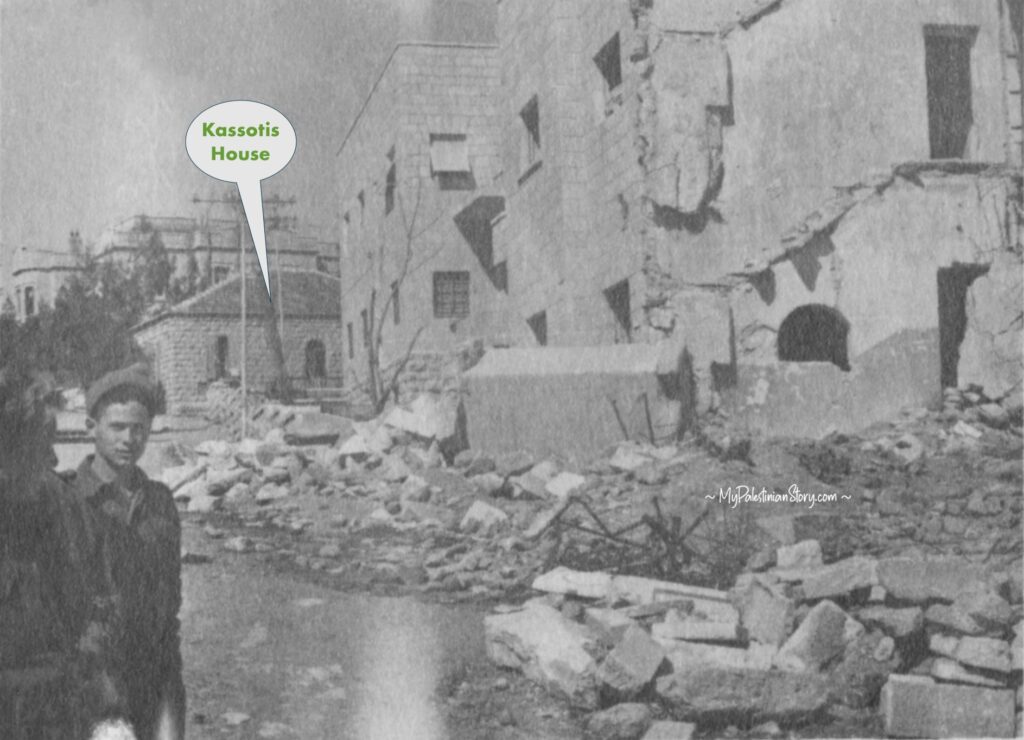

For my mother’s family, the Kassotis, like for the rest of Katamon, 1948 started—literally—with a bang: at 1am on 5 January 1948 the Haganah, the Jewish militia, blew up the Hotel Semiramis, two doors down from the Kassotis house. Around two dozen people were killed. It was the death knell of Katamon—as the explosion was intended to be. People started fleeing and the Kassotis found themselves isolated. So they moved in with the Gaitanopoulos, the family of Vitsa’s sister, Marika, who lived a few blocks away, within one of the security zones the Brits had set up in Jerusalem.

Sandbags were placed in the windows and the families stockpiled provisions—sacs of flour, rice, sugar—while valuables were stored for safekeeping. Soon the Gaitanopoulos left for Egypt, leaving the Kassotis (Yiayia Vitsa, Papou Manolis and their three daughters) in charge of their home in an ever emptier Katamon. Mary, the youngest of three daughters, remembers how her father would take her by the hand every morning and they’d walk around the neighbourhood to see which houses had been destroyed or damaged in the previous day’s attacks.

Manolis could no longer go to Breij. Vasso, the eldest daughter, who worked for NAAFI (Navy, Army and Air Force Institutes) at the time, was picked up by military car until NAAFI shut down its operations in Jerusalem and moved to Cyprus. The middle daughter, Anna (my mother), having finished the Greek gymnasium (high school), was now in her second and last year at the Jerusalem Girls College. But the route to school which was in the Jewish neighbourhood of Rehavia had become too dangerous so she could no longer attend. She was invited along with many others to finish her year and graduate at the Arabic Al-Ummah school in Baqa’a, an area which was relatively trouble-free.

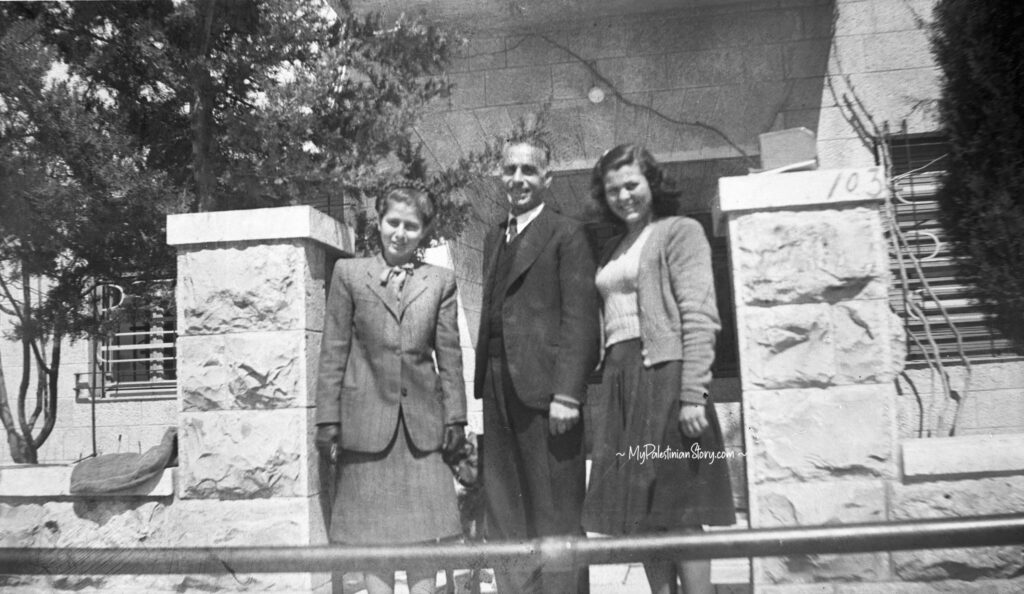

and the director of Al Ummah College, Shukri Harami, at the school – Jerusalem 1948

As the situation deteriorated, particularly following the 9 April 1948 Deir Yasin massacre that terrorised the Palestinian population, the family began to consider their options. Manolis wouldn’t hear of leaving; Vitsa was eager to go somewhere safe, and so was Vasso—now, at 24, the other adult in the family. Vitsa’s siblings eventually all fled to Egypt, and the neighbourhoods of (what was to become) West Jerusalem were emptying fast.

Vasso picked up application forms for emigration to East Africa, South Africa, and Cyprus. A friend advised them against East Africa, didn’t think they’d like it. Vasso’s dream was to go to South Africa. So Vitsa suggested to Manolis: “Why don’t we go to South Africa? You can become a priest and I can be a priest’s wife!” “Because I’m a good Christian,” came the stern reply.

When a NAAFI colleague was leaving for Cyprus, Vasso asked him to contact the abbot of Ayios (Saint) Chrysostomos monastery and let him know that the family wanted to go to the island. The monastery was the exarchy (ie the representative) of the Greek Orthodox Patriarchate of Jerusalem; its abbot, Panaretos, was a good friend of Manolis and had christened my mother in the waters of the Jordan river. Both Vasso and Anna had been to Cyprus on holiday with the Gaitanopoulos who often vacationed there, and loved it. So, a short stay in Cyprus until the fighting subsided and the family could return to Jerusalem seemed like a good plan of action.

One day, Vasso received a telegram from her NAAFI colleague: Get ready for Cyprus! Abbot Panaretos had good relations with the British government of the Colony of Cyprus and had secured them visas, which they required as Greek citizens.

The deadline the British had set for leaving Palestine—15 May 1948—was approaching fast. When Lydda airport became inaccessible, the Kassotis realised they’d have to go to Beirut by land and get a plane from there. By this time, Manolis had practically collapsed and was unable to take any action. Vasso had taken charge and, with the help of my mother, did the rounds of the consulates in Jerusalem to obtain transit visas for Lebanon, Syria, and Transjordan.

Hala Sakakini, daughter of celebrated Palestinian intellectual and educationalist Khalil Sakakini, in her memoir Jerusalem and I, writes that on 29 April the Sakakinis were the last remaining family in Katamon (they fled the following day). They were not: the Kassotis were still there and left on 1 May 1948.

Khalil with his three children–Dumia, Hala and Sari–and his sister Melia

The battle for Katamon, fought around the St Simeon church, near the Kassotis house, was already under way. With tears in their eyes, they bid goodbye to John Schtakleff, Vitsa’s father, who was staying behind to protect the family’s properties from looting which had been rampant. Little did they know how futile that endeavour would prove. With their clothes bundled in bed sheets, and the help of a trusty Arab taxi driver, the Kassotis set off on the long drive to Beirut, via Transjordan and Syria. All along the route, they kept being stopped and asked for their papers; they finally arrived at their destination at night, having travelled without breaks for about twelve hours.

Hotels in Beirut were bursting at the seams with fleeing Palestinians, but Nimmer, the brother-in-law of one of Vitsa’s brothers, managed to find them one room. Manolis and Vitsa slept on the bed, the girls on the floor. In the morning, they woke up to the sound of church bells: it was Greek Orthodox Easter. Nimmer took Manolis to the market to buy suitcases so they could pack their clothing, and after lunch the Kassotis family boarded a plane bound for Cyprus.

Arriving in Cyprus

Today the flight from Beirut to Cyprus takes no more than half an hour. My mother remembers the trip in a Dakota plane taking closer to two hours. It was dark when they arrived at Nicosia airport; at the time the facilities consisted of three Nissen huts.

(Source: James Humphreys CC BY-SA 3.0 – abandonedspaces.org)

They looked for a taxi to take them to Ayios Chrysostomos and luckily a Turkish Cypriot driver knew the place. Nestled in the Pentadaktylos mountain range, close to the small village of Koutsoventis, the monastery is about 15 km north of Nicosia. By the time they reached the monastery it was close to 10 pm and the abbot and his crew were about to call it a day. They were surprised to see the Kassotis—didn’t know when exactly to expect them—but they received them warmly.

The Abbot’s sister, Mrs Paraskevi—same name as my grandmother—was staying at the monastery with a friend of hers. The ladies set the family up in one of the few rooms available. And that’s where the five of them would stay for the next forty days.

– home to the Kassotis family for forty days in 1948

(Photo archive of Manolis Kassotis)

With every passing day, news from Palestine became more dismal. Following the departure of the Brits and the declaration of the Israeli state on 15 May 1948, a full-blown war broke out. All this time the Kassotis thought they were neutral parties to a conflict between Jews and Arabs. They gradually came to realise that this fight for land was between Jews vs everyone else, including themselves, and that they would never be allowed to return to their home and life in Jerusalem. Cyprus was not going to be the temporary refuge they’d imagined: they had now become veritable refugees.

It was an agonising period particularly for my grandparents, Manolis and Vitsa, who felt the burden of responsibility for their girls. The little money they had managed to save and bring with them was dwindling rapidly and their future in this foreign land, with no home, no funds, and no jobs, loomed menacingly.

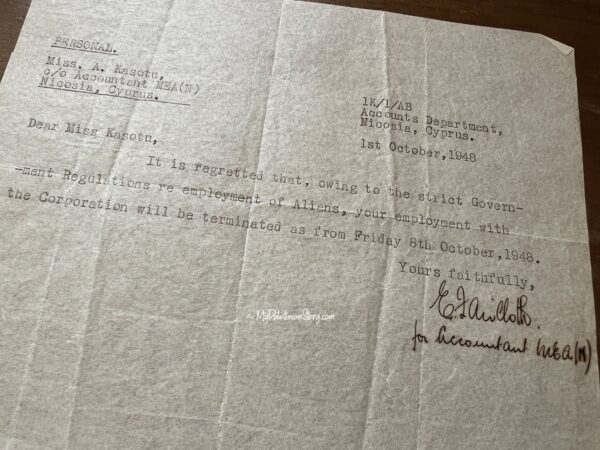

It was time to face reality. Panaretos took them to Nicosia where they hoped to find jobs. Manolis became very sick, developed diabetes, and was unable to work. Vasso was the first to find work, first at NAAFI, her old employer in Jerusalem, and then at a petroleum company. Anna was also hired at NAAFI but a few months later a letter put a stop to that: “It is regretted that, owing to the strict Government Regulations re employment of Aliens, your employment with the Corporation will be terminated as from Friday 8th October, 1948.” Anna had no choice but to go “underground”. She found a lower-paying job with a company of clothing merchants who employed her to do their English correspondence and paid her under the table.

In January 1949, a letter from the authorities rejected Vasso’s application “to take up employment in Cyprus…” suggesting that “if your family’s funds do not suffice… you and your family should make arrangements to return to Greece” (a place they never lived in, not even visited). In mid-April followed a notice “to leave the Colony” by the end of July or be prosecuted. I can’t imagine how far down their stomachs their hearts must have sunk upon reading that.

But finally the Kassotis got a couple of lucky breaks. In the summer of 1949 the Consul General of Greece Alexis Liatis contacted Papou Manolis. He had been urged by another Greek diplomat, Dimitris Papas, who had been consul in Jerusalem and knew the family well, to do whatever he could to help them. So Liatis offered Papou a job at the consulate. However, Manolis wasn’t sufficiently qualified because, with Cyprus still being a British colony, the job required excellent knowledge of English which Manolis didn’t have. So he suggested that they hire his middle daughter, Anna, instead. She had graduated from a Greek gymnasium and then done two years in an English school, and as a result had excellent command of both Greek and English. Mum started at the Greek consulate in June 1949 on a trial basis and by the end of the year was taken on permanently for what would turn out to be a nearly forty-year career. (After Cyprus’s independence, an Embassy was added to the consulate and that’s where she worked until her retirement in 1988. But that’s a whole different story—albeit a fascinating one.)

Then Vasso got engaged to a handsome young Cypriot, Stelios, a bank employee, she met at a ball; they married in September 1949. Vasso and Anna had been fortunate to make friends early on. In fact almost as soon as they arrived at Ayios Chrysostomos monastery they bumped into a group of young people who were on a day trip from Nicosia with an excursion club: a mix of Cypriots and other Palestinian Greeks who had come to the island earlier, including George Louisidis (who had been my mother’s boyfriend in Jerusalem and subsequently married another Greek Jerusalemite). Some of them and other people they met in Nicosia through them became life-long friends—and a couple of them, husbands! (And as for George Louisides, his children have been life-long friends of mine, too.)

Through her husband, Vasso got British citizenship. Now married to a Cypriot, she could work openly so she went back to NAAFI. At last the family had sufficient funds and, with one of them married to a local, they were allowed to stay on in Cyprus indefinitely.

– Nicosia, Sep 1948,

Settling in Cyprus

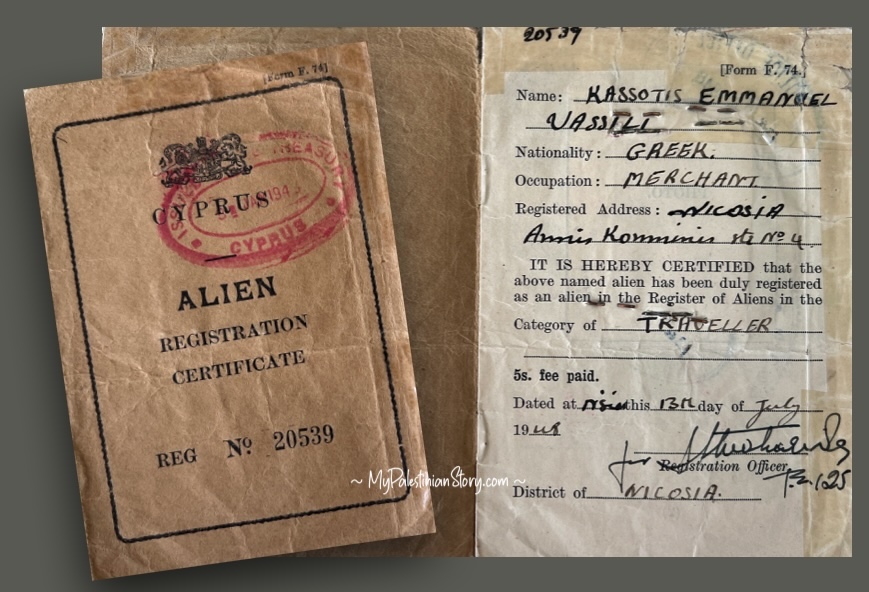

During this time, they had been moving around from one place to another. Aunt Mary remembers that at first they lived for a while in a hotel in Ledra street (the commercial centre at the time) where she had been quite ill and was looked after by the Christophorou family, friends from Jerusalem. In one of the places they rented, Vasso remembers her father being so ill that for three months, only Vitsa could enter his bedroom. When Manolis registered with the police as an alien in July 1948, their address was Annis Komninis Street. His Alien Registration booklet shows a different address at practically every check-in with the police: Passiadou St. later on in 1948, Nicosia-Limassol Road in 1949, Frederikis St in 1950.

In this last address they lived with the Gaitanopoulos family who in the meantime also moved to Cyprus from Egypt. Efthymios Gaitanopoulos (Marika’s husband) had a good job with Gresham Insurance so they two families co-habited so as to ease the Kassotis’s burden. They shared a big house and the girls were thrilled to be reunited with their cousins who had been their closest friends in Jerusalem. Mary and her cousins were enrolled at the American Academy to continue their secondary education.

After his two eldest daughters had been settled in their jobs, Manolis was finally able to secure a job himself. He was employed to manage Strakka, a large estate in Deftera, just outside Nicosia. The estate, which dates back to Venetian times, was acquired by the wealthy Leventis family in the 1940s. Although tiny in comparison to Breij, the estate Manolis leased and managed in Palestine, it gave my grandfather the opportunity to be in an environment he loved and understood—working with the land, with olive and citrus trees—as well as the feeling that he was at last contributing to the upkeep of his family.

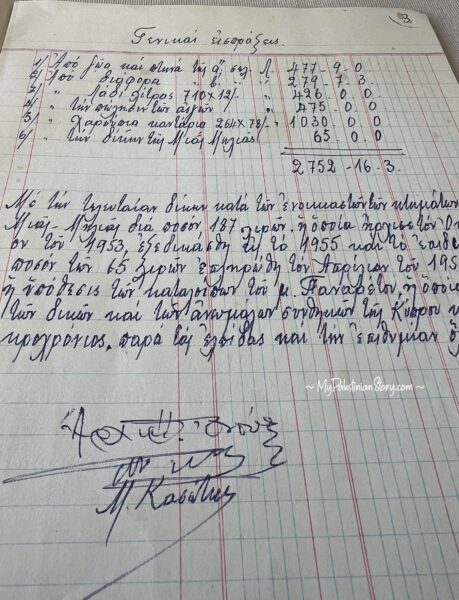

My mother’s blue binder of her father’s papers (mentioned in Part 1) reveals that he had at least two more jobs. A letter by Manolis’s good friend Abbot Panaretos of Ayios Chrysostomos, dated January 1953, and addressed to the authorities, proposed to hire, on behalf of the Exarchy (Greek Orthodox Patriarchate representation in Cyprus), Manolis Kassotis, specialist in agriculture and animal husbandry, for a monthly wage of twenty pounds (CY£ 20). Panaretos wrote a letter of recommendation to add to the one written by Angelos Antippas, MBE, who had been the president of the Greek Community of Jerusalem and also head of the British Secretariat (and whose daughter was killed in the July 1946 King David Hotel bombing). Both referees extolled Manolis’s character, technical knowhow and management skills, exemplified by his successful management of the vast estate of Breij over three decades.

The application was successful. A ledger Manolis kept of the proceeds and expenses of the monastery (eg sale of animals and agriculture produce, rents etc) shows that this particular engagement lasted till 1961.

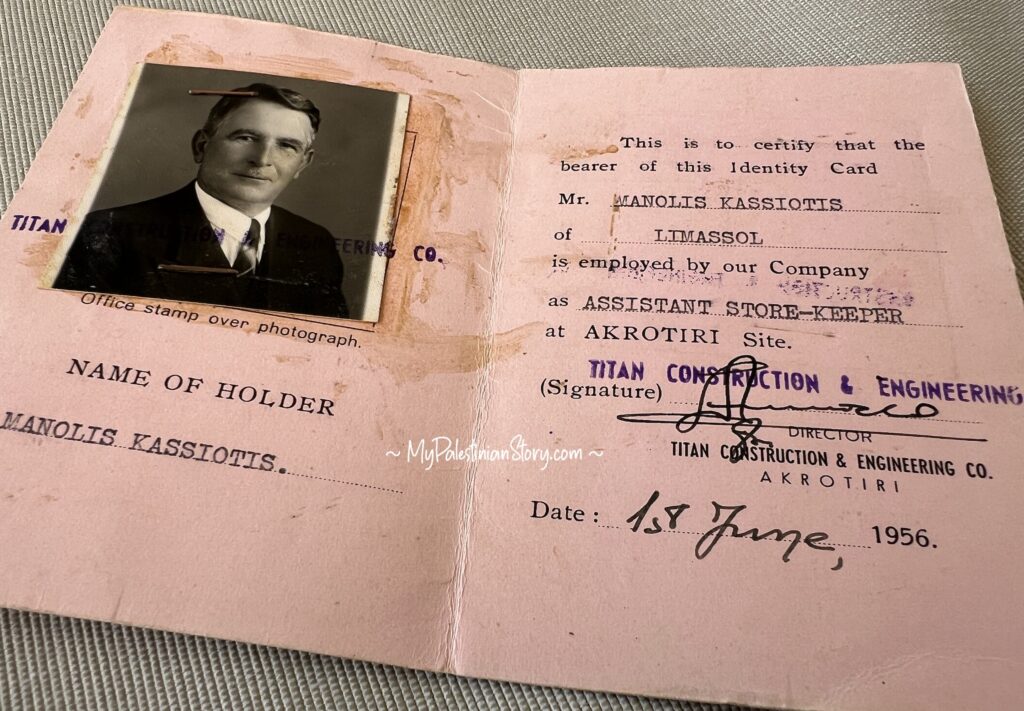

But during that time he seemed to have also spent some time as assistant store keeper for Titan Construction & Engineering Co., at Akrotiri, the British base west of Limassol. This one is a bit mysterious because I’ve never heard it mentioned—how long he did this, whether he commuted or lived at Akrotiri (or Limassol) for a spell. The only evidence I have is an identity card, dated 1 June 1956, with no renewals. A quick Google search reveals that a company by that name was registered in 1949 by two members of the Paraskevaides and Joannou families, the well-known J&P construction tycoons that in times past had built half of the Middle East and Persian Gulf. So, I’m guessing someone must have known someone and put in a word for Manolis.

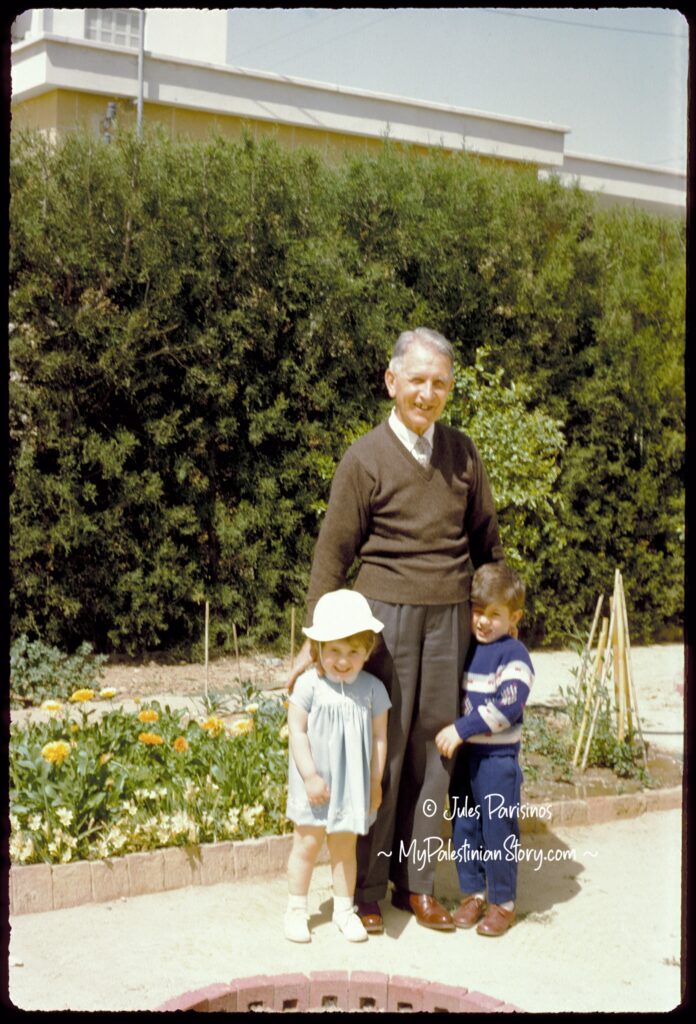

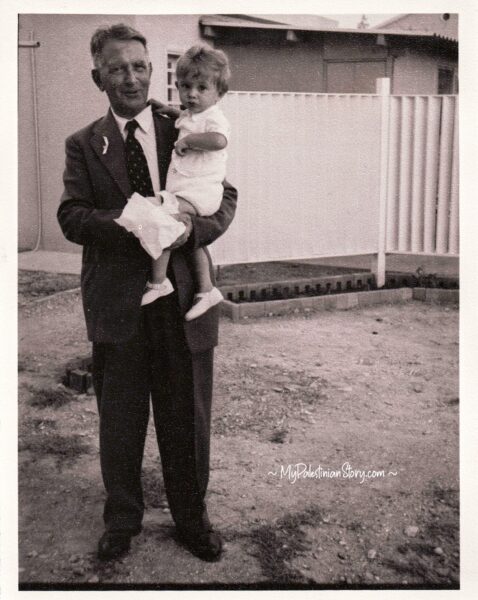

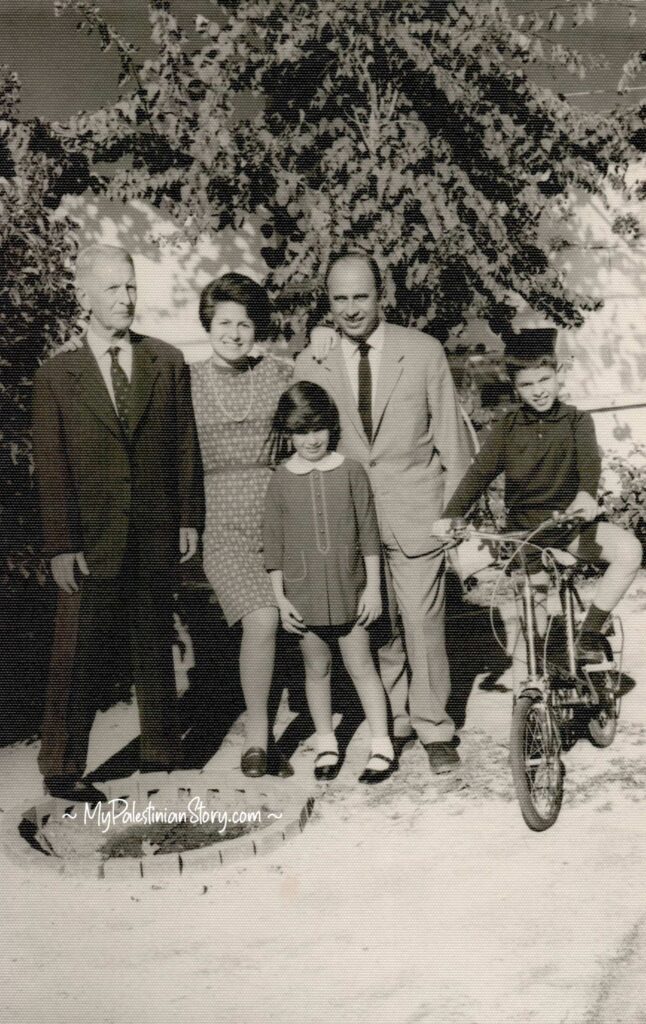

The only job in which I actually do remember Papou—other than babysitting all his grandchildren—was at the Department of Agriculture of the Cyprus Republic, ie in the 1960s. In November 1957 Anna married Jules Parisinos (hence my brother and me!) My father was an agronomist and senior officer at the Department of Agriculture, Ministry of Agriculture and Natural Resources, so somehow he arranged a job for Papou. Which explains the 1901 year of birth shown in the Social Security records. Dad would have been hard-pressed to advocate for a position for a man in his 70s.

Vitsa embracing her daughter, while Manolis looks on, clearly moved, as the groom kisses his hand.

Marika Gaitanopoulou (R) sorting out the bride’s veil

Both my brother and I have memories of Papou at this job. The Department was located behind our primary school so we’d finish school and walk over to Dad’s office who would bring us home. In our first years at school, Papou would be there working too. But even with a 1901 birth year, it would be difficult to hold on to that position past the mid-1960s.

Manolis had a hard time accepting that everything he’d built in Jerusalem was gone forever. A couple of circular letters from the Greek Consulate in Israel must have given him some hope that he could claim compensation for his losses so in November 1949 he applied to the colonial authorities for a visa to travel to Palestine to “try through the Patriarchate to get compensation [for Breij] from the Israel Government. The estate has now been taken over by the Israel Government and on it stand personal installations and machinery of considerable value which I desire to recover if possible.” I don’t know if the visa was ever granted but I do know that Papou never went back to Palestine. A later attempt to claim for the Katamon house produced copious amounts of correspondence over several years and no results.

There is no doubt that of all the Kassotis, Papou Manolis was the one hardest hit by the loss of their homeland, their home and their living. He never came to terms with it. I can still hear my mother on the first day of the Turkish invasion of Cyprus in July 1974, as we all huddled on the floor of our living room hoping to stay out of the way of bombs and bullets, saying: “Thank goodness your grandfather is no longer alive to go through this twice.” She knew it would have been too much for him.

Not that it was easy for the rest of them. They all missed their home terribly and continued to talk about it constantly for the rest of their lives. The girls struggled as newly minted bread-winners for the family but also enjoyed themselves with outings, excursions and making new friends. They eventually all married well and built families. Vitsa proved more resilient (dare I say, as women often are in crises?) Beginning in the early 1960s, she embarked on a career as cook and confectioner which kept her quite busy and was an outlet for her creativity. But Manolis just couldn’t come to terms with his loss. I can only imagine what it must have been like for a man of his generation, in his fifties, with a family to support and having built a successful business and home, to lose it all overnight and to have to rely on his young daughters and subsequently their husbands also, to support him financially.

This resulted in tensions at home, and the girls had to separate their parents, although they still functioned as a family and loved each other. Yiayia got a place of her own early on which was then used as a workshop too, and Papou went to live with Vasso to take care of her boys. Then, when my brother and I arrived at the scene, Papou came to live with us, and Vitsa would stay at Mary’s mostly. In fact, both grandparents were moved by the sisters strategically on the baby-sitting chessboard to ensure that all kids were well taken care of. If my parents were travelling, Yiayia would join Papou at our place to help with looking after us. When Mary and her eldest son went to Beirut, and Yiayia was with us in Famagusta, Papou would go stay with Mary’s youngest, and so on.

(Photo by Jules Parisinos)

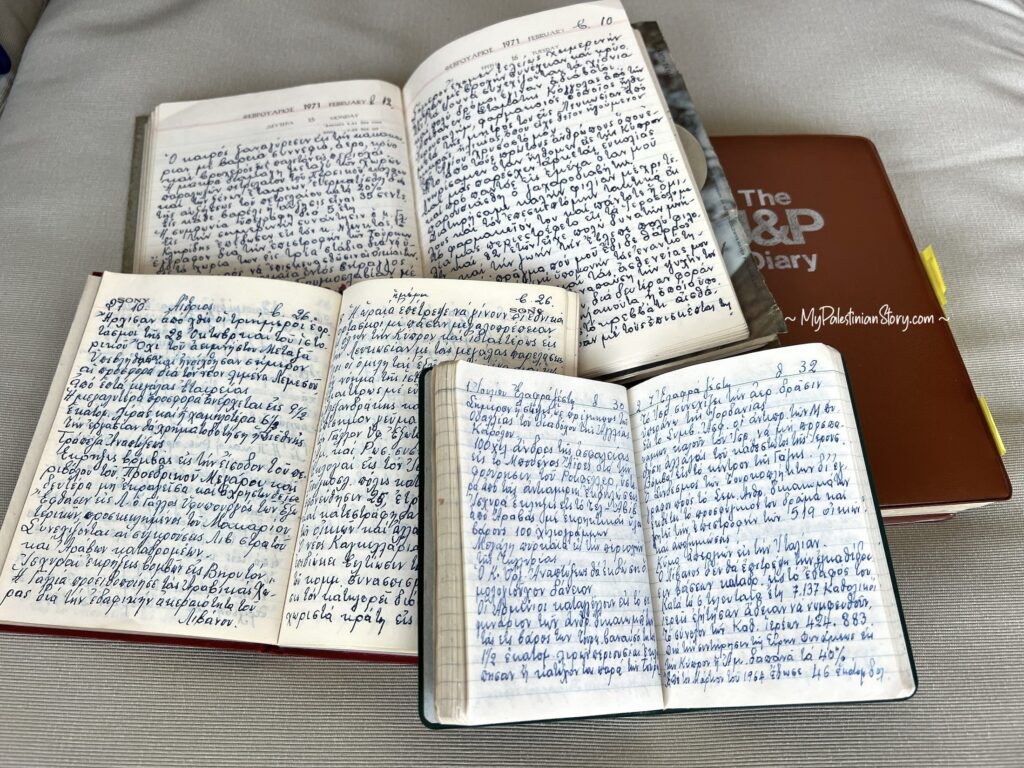

Papou’s Diaries

For the last few years of his life, Papou Manolis kept a diary. The other day, having read through the ones from mid-1969 to the spring of 1971, I mentioned them to Aunt Mary and wondered if there might be more. She looked at me cryptically for a moment and then produced another one from her bedside table. This was a small red booklet and it was clearly the start of this practice. With a few notes here and there in the beginning, by mid-1969 it had become a daily ritual. For the last two years, he used larger notebooks, the type of diaries companies distributed as promotional material back in the day.

Each page was filled to the very last line with his precise handwriting, which looked a bit like him—tall and slim, always upright and clean. He wrote in katharevousa—an archaic form of Modern Greek.

He’d unfailingly start with the weather: the temperature on the top right-hand corner, and a line about heat, cold, rain, wind. He’d report on his health which continued to give him much trouble. In addition to diabetes, he suffered from arthritis, and various other maladies. Visits to the doctors were frequent as were medical tests and prescriptions issued and consumed. On one occasion he commented that his meagre pension was all spent on medications. Knowing what we know today about mental health, there is no doubt in my mind that Papou suffered from depression which may well have been the cause of at least some of his many health complaints.

Each day’s entry was a stream of intermingled topics, often with no paragraphs. This grandson is at home with a cold, Archbishop Makarios made such-and-such declaration, flood in this country, earthquake in the other, attacks in the Middle East, fighting in Vietnam. Short and to the point, all very matter-of-fact, with editorial comments few and far between.

His current affairs reporting would become more extensive and enthusiastic with every Apollo mission to space. He followed each closely, day after day, and was hugely relieved when the “heroic” astronauts returned safely to earth.

He’d write about the highlights of the day’s activities, if there were any. Which grandchild had the measles, who had the flu, who was coughing, who was sneezing; which son-in-law or couple was travelling out of town or abroad. His references to family members were affectionate: our Vitsa, our Jenny, our Marika.

His grandchildren held a special place in his heart. He was very fond of his older grandsons, Vasso’s three, who were his first charges. He was pleased to see how the eldest was turning into a nice young man; he’d gifted a dictionary to the youngest one as he did to my brother. But when it came to his two youngest grandchildren, Mary’s boys, his love for them spilled off the pages. He practically pined for “our babies”. Three days without seeing them was too long. When our house was under a twenty-two-day quarantine due to my brother and I getting chicken pox in consecutive manner, and as a result he was banned from visiting Mary and couldn’t visit the little ones, he was downright miserable.

But then there was me: the sole girl in the family. In 1969, when I was only eight years old, he was saddened and upset with me because I was becoming “quite insolent, stubborn, and other things”. Poor, Papou. He seemed to have the same expectations of me as he had of his own daughters when they were young, back in the 1930s and 40s, and he dealt with them with a strictness that Vasso once described as almost Dickensian. I don’t think Papou was ready for a world of independent women who have their own mind. Nor was child psychology in his radar. I wonder, if he were still alive today, could he have recognised and/or appreciated a badass of a woman? I’d like to think he would. Papou was very much a product of his generation, his background and his upbringing but ultimately he was of a deeply kind and loving nature.

Papou spent a lot of time at home, often in ill health, alone with his books (mostly religious) or watching TV (hence all the news reporting). He would work in the garden, watering, planting flowers, and he’d go to Mary’s to do the same. He relished visits to and from old Jerusalemite friends who were also shipwrecked on Cyprus, like the Saoulis and the Whitfields; together they reminisced about “sweet, unforgettable Jerusalem”. That was his favourite topic. Many an hour was passed by my brother and me, on Papou’s single bed, in his tiny room, listening, wide-eyed, to his stories of Breij and Jerusalem, lapping them up. A big part of my love for family history I owe to him. And my brother credits Papou for his own diary-keeping practice.

Yiayia Vitsa in the middle, Mum at the back, on the couch

(Photo by Jules Parisinos)

Attending service every Sunday morning was also a source of deep satisfaction. If either his health or that of his charges (us, grandchildren) prevented him from attending in person, he’d still follow the service on the state radio (this was Cyprus after all, a country no-one could ever accuse of being strictly secular!) but it wasn’t quite the same for him as being physically present.

On special occasions—birthdays, namedays and the like—when the family would get together, he’d express great joy and sometimes indulge his introspection on paper. On Saturday, 14 March, 1970, he wrote:

Today is the birthday of our Vitsa and with much emotion I recall the old joyful and happy years of our life in Jerusalem; especially the days and years we lived at Breij, where amidst so much joy and the love possessed by youth, the small clouds of life would quickly disperse; and it never crossed our minds and thoughts that the passage of time would have such adverse effects and repercussions on our marital status.

I thank the All-Merciful God that our degrading fate in Cyprus became the cause of the happy marriages of our daughters; and today we live for them and from them, and thanks to their good husbands we will have that possibility till the end of our lives.

I feel and seek joy in the health and happiness of our daughters, of their husbands, and of our seven beautiful grandchildren. At Anna’s house we celebrated Vitsa’s birthday with great joy … and I was deeply moved by the lively expressions of love.

Two weeks before he died, he wrote a letter to his wife and daughters. Sensing that his end was near, he wanted to make his last wishes known and dispense some advice. His few savings were to be given to Vitsa as he felt that a portion of his small pension belonged to her and he had made a point of setting it aside specifically. His clothes were to be cleaned and given to an old people’s home that he named. He closed with:

Bury me in a frugal manner. Every expense on the tomb is an error and a folly. Anything good or bad I did is a good or bad memory, and God gave us the means and the time to be judged according to our deeds.

Protect and help Mother who is tired.

Live joyfully, with love for each other and for your husbands, have patience and tolerance with your children, tame your nerves in order to avoid the negative consequences.

On Saturday 3 April 1971, he wrote in his diary at length about the rainy day which caused a plane arriving from Athens to be rerouted to Istanbul as poor visibility prevented it from landing in Nicosia. His two last sentences were about having enjoyed lunch with Vasso’s husband and youngest son, and the letters we received at home from Vasso and Anna who were both abroad. “We were all pleased.”

The following morning I found him dead on our kitchen floor.

Papou Manolis is still very much alive in the memories of all seven of his beautiful grandchildren, his one remaining daughter, as well as his relatives in Samos whom I had the pleasure of discovering in the summer of 2006. Some day I will write about that too. ❖

This family history is wonderful with all its downs and ups and the close community of the Church is revealed so clearly as well as the close relationship of this family who shouldered each other. Thank you again for making this part of history alive. Please continue. Like me, I think, many people are reminiscing and missing the old days.

Many thanks, Nadia, for reading and your kind comments. More family stories to come soon…

Marina – dearest cousin – This tugs at my heart bringing me tears . Pure and simple. I loved reading ever word! And as for Theo Manolis’s admiration towards the Apollo astronauts- how remarkable that Alex married into that family. But I digress –

Your tribute is very touching – rich with golden text and story-telling. You are very gifted. I am grateful I had the opportunity to have met him before his passing.

Thanking you for sharing – xo

Many thanks, Corinna! So glad you liked it.

Thank so much, Dorit! Much appreciated!

This is such a moving account of difficult but also beautiful life your grandparents, mom and aunts built for themselves amidst war, dispossession and trauma. Thank you for sharing it with us, and keep being the kick-ass woman that you are. I am pretty sure that he would appreciate it now.

Marina, totally heartbreaking. You are a masterful bookwriter. What an endeavor and so well written. A credit to you dear friend x

This means a lot, James! Thank you!

Hi Marina . We tripped over your publication by accident a few hours ago . I was born in Jerusalem in 1946 . My father worked for the British Colonial Service and spoke many languages . We lost our house and escaped to Cyprus in 1948

I remember Gaitanopulos and his family . They were very good friends of ours in Nicosia .

Thank you for the historical memories . I will read with great interest . I now live in New Zealand post the Enosis crisis in Cyprus .

Dimitri Cocorempas

Many thanks for writing, Dimitri. I’ve heard your family name in the stories about the Greek community of Jerusalem and I’m glad to connect with you. I’ll drop you a line via email.