~ The story of my grandfather Manolis Kassotis—Part 1/2 ~

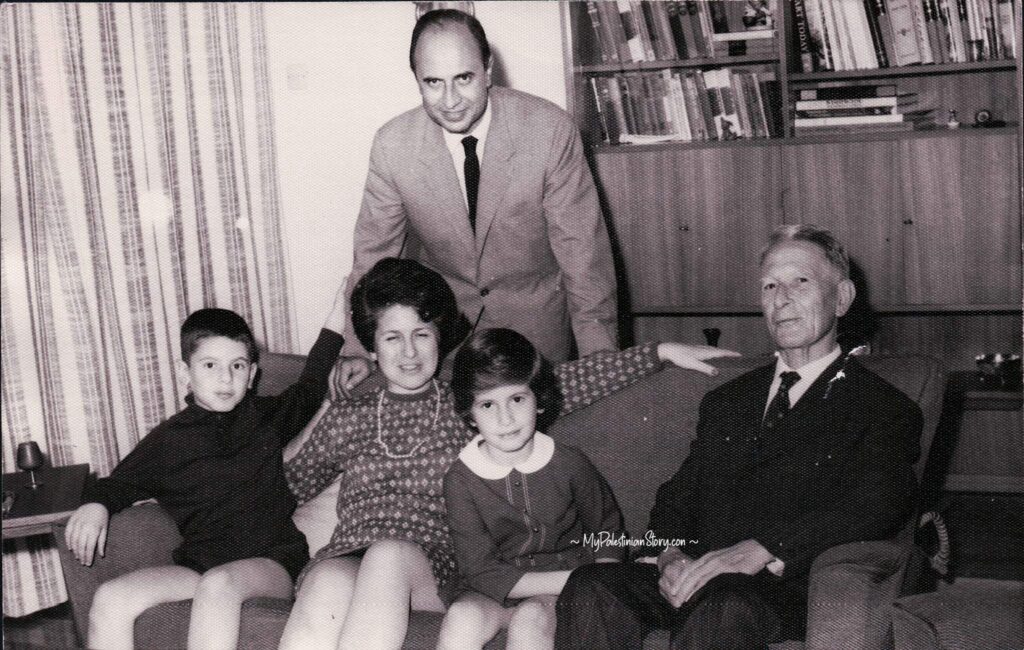

My grandfather’s death was never recorded officially. He died on 5 April 1971 in our home in Nicosia. He used to live with us while our grandmother, Yiayia Vitsa, lived with the Eftys (Efthyvoulou), their youngest daughter’s family. On that day, both grandparents were at our home as our parents had gone abroad for two weeks and had left my brother (age 12) and myself (10) in the care of the elders.

Yiayia took off early in the morning to go to her workshop where she did her baking magic and Papou (Papoú is grandfather in Greek) dispatched me to the letterbox, a block away, to post a letter for him. I still remember crossing the side street on my bike and seeing the back of Yiayia at the far end of the road as she walked away, stooped on her cane. For some reason my brain snapped that image and locked it in place even though it preceded the shock that was to follow. I slid the envelope into the letter box and rode back.

Papou Manolis was lying unconscious on the kitchen floor, a small pool of blood around his head. Not daring to approach, I shouted out at my brother who was upstairs: “Christodoule! Something’s happened to Papou!” Papou had been in a foul mood that morning and had told me off for some trivial non-reason which caused my ten-year-old brain to send out warning signals: Best to leave him alone. What if I try to wake him and he gets mad at me again? But my gut, in its ageless wisdom, knew something was seriously amiss.

Christodoulos, being all of two years older, took charge of the situation: he poured a jug of water on Papou in an attempt to revive him. No dice.

We rang the Eftys—Aunt Mary (Μum’s youngest sister) and Uncle Shurik (Alex Efthyvoulou)—and reported the problem. Shurik dashed over in no time, in their little Fiat, and after a quick look at Papou on the kitchen floor, ran the block-and-a-half to Dr Fessas’s house, to fetch him. Papou was proclaimed dead of cardiac arrest. It seems that he was standing in front of the kitchen sink when his heart gave out on him and he hit his forehead on the sharp stainless-steel corner as he collapsed, which resulted in all that messy blood.

I have a vague recollection of being taken to the Eftys afterwards, for the rest of the day. And I’m guessing that Yiayia must have stayed with us at home until our parents’s return a couple of days later. But Papou Manolis was no longer in our lives.

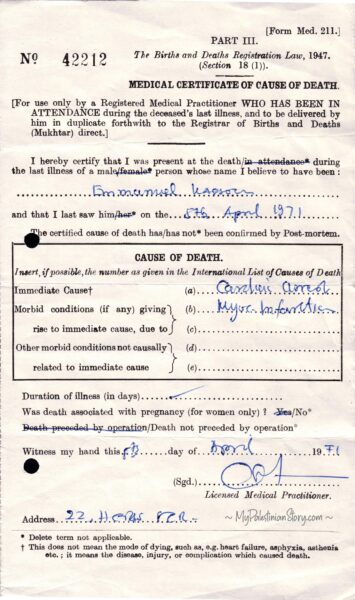

Digitising a Death

In late August 2017 I looked for his death certificate but did not find a copy in the blue binder that my mother so meticulously kept of her father’s papers. Only a Medical Certificate of Cause of Death—the paper issued by Dr Fessas. I thought I’d go get a copy from the Citizens’ Service Centre (CSC) known for its super-efficient service, but it turned out to be a not-so-straightforward proposition. I stumped them with the 45+ year-old medical certificate which offered no details about my grandfather other than the date and cause of his death. After a half-hour wait which included a couple of phone calls by them to the District Office, I was told that that’s where I had to apply since no digital record of my grandfather existed at the CSC. My grandfather was most definitely of the analogue era!

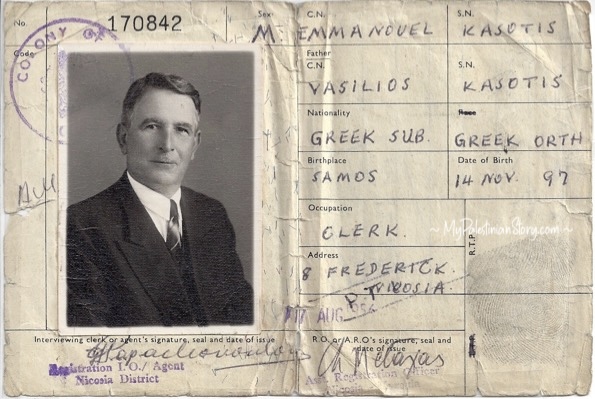

Two days later I visited the Nicosia District Office. I presented the Medical Certificate along with Papou’s Cyprus ID, which I fished out of the binder, duly stamped by the British Colonial authorities, having been issued before Cyprus’s 1960 independence. I figured that it might help since it had all the important information I had been asked for at the CSC: date and place of birth etc. It certainly made my request look more legit—but got me no further.

The clerk took my documents, checked the computer and, once again finding nothing, said she’d have to go search the paper archives manually. I wondered to myself if I should have brought a picnic basket but she was back before long and informed me that Papou’s death had never been filed. Consequently, in order to get a death certificate, a statement had to be made in court under oath to the effect that the person in question was in fact dead. She gave me the form that had to be approved and signed by a court registrar (Πρωτοκολλητή), along with a second, longer one that would provide the District Office with Papou’s profile details to be entered in their system so the death certificate could be issued.

I bumped into my brother later that day and filled him in on my bureaucratic adventures. He wondered why Mum and her two sisters didn’t take the trouble to get a death certificate. “What was the point?” I suggested. The sisters had no reason to take a step that would only cost time and confer no benefits. There was no official will or administration of an estate. Papou died without a penny to his name—poorer than the proverbial church mouse. In a hand-written letter he left for his daughters, he asked that his few clothes be cleaned and given to the poor. Or perhaps the sisters thought that not being a Cypriot citizen, there was no need for it.

I got working on the forms. The court statement was short.

- Full Name of the Deceased: My grandfather was Emmanuel (Manolis) Kassotis (Εμμανουήλ Κασώτης).

- Date of Death: 5 April 1971

- Place of Death: Our home in Nicosia

- Creed: Greek Orthodox. And how! Papou was of ecclesiastical pedigree. Not only was his father a priest but his uncle was the Greek Orthodox Patriarch of Jerusalem Damianos I—which is how Papou found himself in Jerusalem. The Patriarch took him under his wing, presumably when Manolis’s father died, and moved him to Jerusalem.

- Date of Birth or Age: That’s where things got tricky. His ID, issued by the government of the Cyprus Colony, shows 14 November 1897 as his date of birth. An ID card in Arabic, issued by the “National Jerusalem Committee” in 1948, puts his age at 56, ie year of birth 1892. That is practically the same as what his Greek passport and a certificate of expat registration from the Greek consulate in Nicosia, also dated 1948, state as his year of birth: 1893. But an older certificate issued in his Greek hometown has him as born on 5 August 1901. A nine-year spread is not trivial. I wondered in which direction the desired effect was intended to be: older or younger? I opted for the date shown in his Greek passport which made more sense to me.

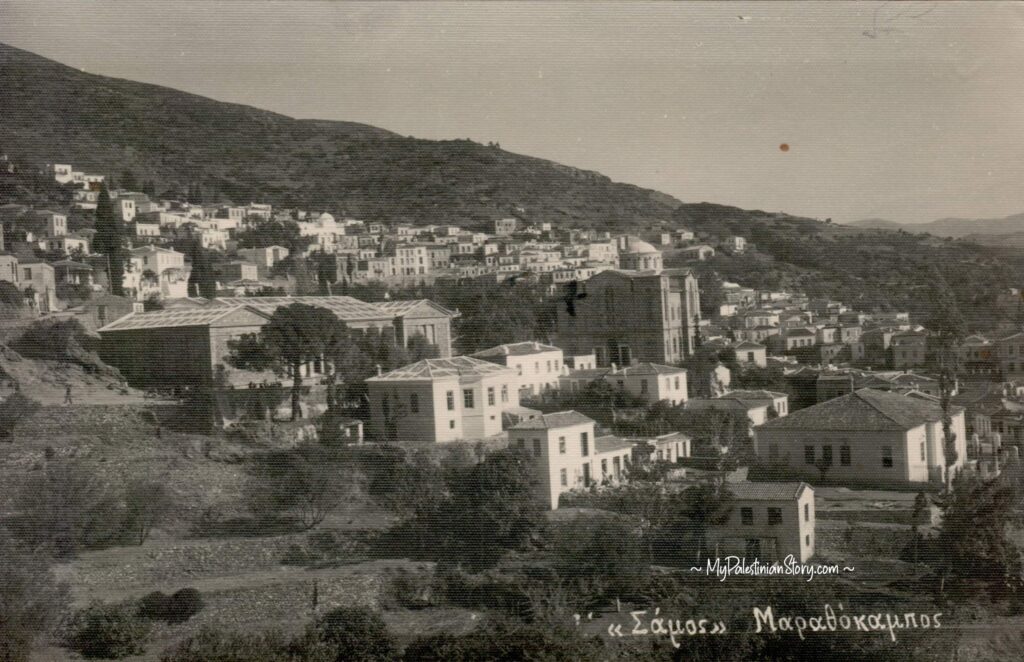

- Place of Birth: The village/town of Marathocambos on the Greek island of Samos.

- Father’s Full Name: Vassilios Kassotis (Βασίλειος Κασώτης), known as Papa-Vassilis, ie Father Vassilis.

- Mother’s Full Name: Providing a surname was a stretch but I knew her first name was Kyrani (Κυράννη).

- Signed: Marina Parisinou. That’s me, swearing that this person’s death “had never been recorded in the Registry of the District Officer due to negligence.”Not mine!

The following day, as I rode my bike to the Nicosia Court house which is only a few blocks away from my flat, I contemplated the poetry of me being once again the one dealing with Papou’s death. I was the one who found him dead so many years ago and here I was several decades later about to swear to the authorities that that was indeed so.

After purchasing stamps worth €4, I was directed to the Registrar’s office, a chaotic room overflowing with piles of paper binders, tied with string, scattered all over, with smells dating all the way back to the British empire. Slow morning—thankfully—so a clerk took the form immediately and got to work without so much as a glance at me. On the counter, a Bible and a Qur’an were ready to be of service in attesting to the truth. It barely took a minute for the girl to scribble whatever on the form and I heard the familiar, business-concluding sound of the stamp: bang, bang! Almost as an afterthought, she finally looked up at me: “You swear, right?” “Yes, of course”, I replied earnestly. Neither of the holy books was involved in the transaction, my beliefs thus being accurately represented.

From there, it was back to the District Office. The lady remembered me, checked my papers, and directed me to her supervisor’s office. He checked his computer, too, and—surprise, surprise—he found Papou’s name in the records of Social Security. There his date of birth was stated as 1901. I explained that there was some confusion but the man was unperturbed. “Doesn’t really matter”, he said. Why would it? Papou had been dead for 46 years. At last his death was duly digitised.

Life in Palestine

In 1995, in response to my many questions about Papou, my mother sat down and wrote in longhand a 45-page double-spaced narrative of her memories of her father and their life in Palestine more generally. She intended to continue at some point but never got round to it. I also have a copy of my youngest cousin Dimitris’s school project on the family history of his mother’s side, which he wrote after interviewing Yiayia in 1981, when he was a third-grader at the English School (secondary school). Then there’s the thick blue binder my mother put together which contains all sorts of treasures. And finally there are four diaries of my grandfather’s from the last years of his life. All these documents along with the oral history interviews with family members that I’ve conducted over the years allow me to piece together the story of my grandfather, albeit somewhat warily, mindful of the traps of oral history and incomplete records.

Manolis was 10 or 12 years old when Patriarch Damianos took him to Jerusalem. He lived in the monastery and attended the school of the Patriarchate which, if I’m not mistaken, is the one adjacent to the Greek Orthodox cemetery on Mt Zion where my great-great-grandfather (on my grandmother’s side) George Schtakleff is buried.

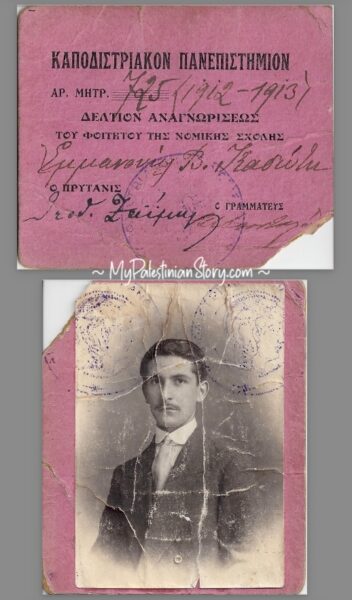

The Patriarch then sent Manolis to Athens to pursue university studies. In 1911 he was enrolled to study law at the Kapodistrian University in Athens. (Which is one of the reasons I thought 1893 made more sense as his birth year: he would have been 18, which is a typical age to go to uni.) After a year or two, having apparently decided that lawyers were all crooks, he switched his studies to agriculture. He spent roughly three years in Athens and returned to Jerusalem without graduating. My mother said it’s because Damianos wanted him by his side but I suspect it had something to do with the outbreak of the First World War in 1914. The last record I have of his years in law school is a student ID for the academic year 1912-13.

For the next couple of years Manolis assisted his uncle, Patriarch Damianos, in the latter’s private office. Then Damianos put him in charge of a vast estate owned by the Patriarchate, which Manolis eventually leased for himself, possibly beginning in 1918. Located at the village of Al-Burayj or Breij (which in Greek they called Bretz or even Prets—Μπρετζ/Πρετς), some 28 kilometres west of Jerusalem, it covered 18 square kilometres (for comparison purposes, New York City’s Central Park is 3.4 square kilometres); it included a Greek Orthodox monastery, a holiday home for the Patriarch (where Manolis and subsequently his family lived), a farm, orchards, woodlands. Part of the land was rented to the villagers for cultivation and Papou collected the customary tithe. He was well liked by the villagers who saw him not only as their landlord but also as their doctor, their teacher, and their judge, even if his Arabic was rather poor (but still better than his English!)

According to his Government of Palestine ID, Manolis was tall (5 foot, 8 inches or 173 cm), of medium built, with dark brown eyes and black hair. His student photo shows him sporting a thin moustache which in later years was converted to toothbrush style.

In the early 1920s, his eye caught a beautiful young girl in the Greek colony: with blonde hair, blue eyes, and fair Slavic complexion, Paraskevi (aka Vitsa) Schtakleff looked “like a mirage”, according to a family friend who remembered her playing the piano at the Greek Club (Λέσχη). Her Bulgarian (Macedonian?) father, John (aka Hanna) Schtakleff had a flour mill and bakery that supplied the Ottoman army with flour and bread. Her mother, Eugenie Agathopoulou, was a Greek actress from Constantinople who had come to Jerusalem with her father’s itinerant theatre troupe. Vitsa, eldest of five children, attended the French Notre Dame de Sion school, spoke Greek, French, and Arabic, and was an accomplished piano player who was often called upon to entertain her father’s business guests.

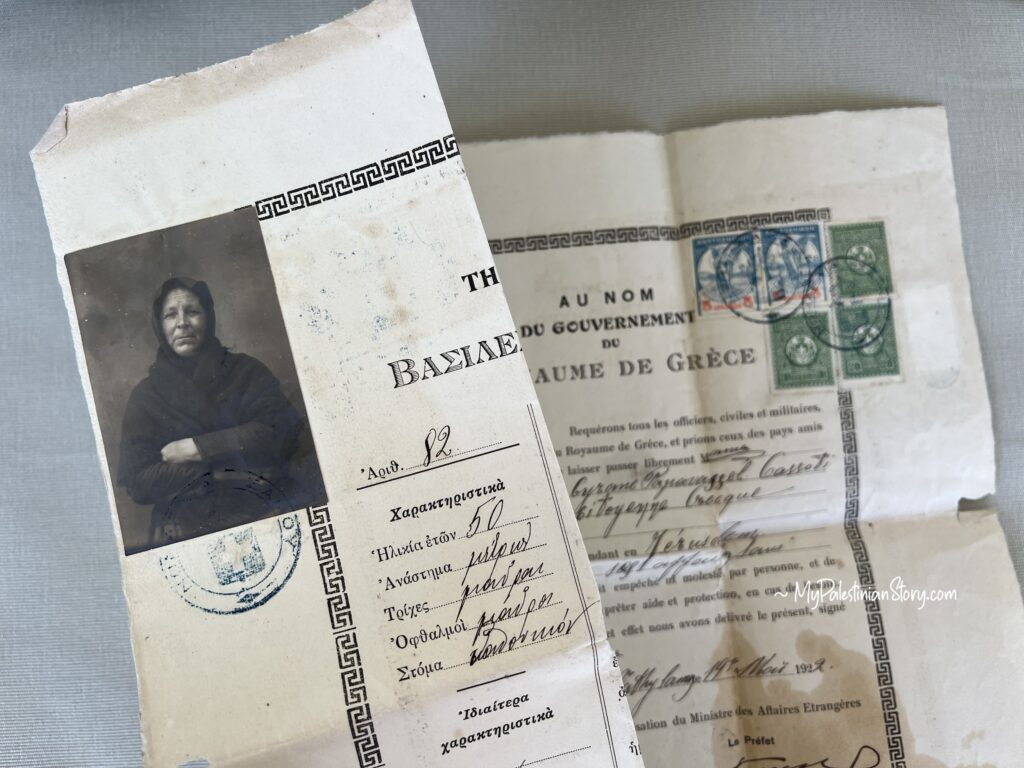

It must have been early 1922 when Manolis and Vitsa bumped into each other in the street and she informed him that she would soon be leaving Jerusalem. With the advent of the Brits in Jerusalem, John’s fortunes had plummeted. Hoping to collect on his Ottoman debts, he was moving the family to Constantinople. Manolis was dismayed. Wasting no time, he sought out her father and asked for her hand which he was duly granted. When word reached Samos that her good Greek boy would be marrying a Bulgarian, Kyrani resolved to put a stop to this ethnic affront and rushed to Jerusalem. She had a laissez-passer document issued in May 1922 and arrived in Palestine the following month. But Manolis would have none of it.

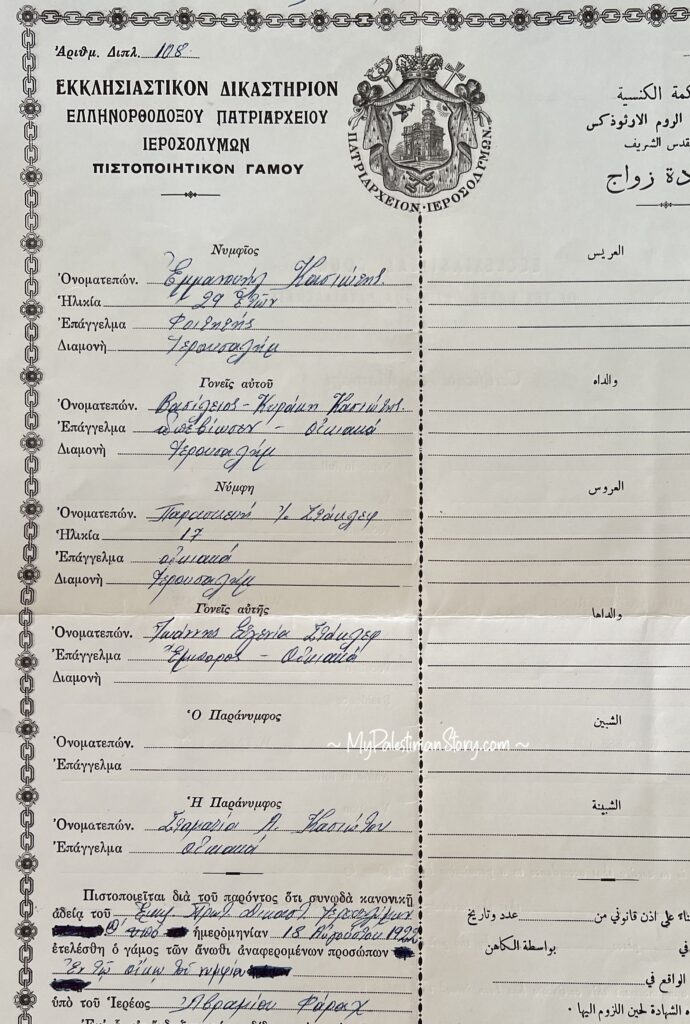

On 18 August 1922 Emmanuel Kassotis, aged 29, and Paraskevi Schtakleff, at 17, fresh out of school, were married by Father Ibrahim Farah in the groom’s house in Jerusalem. (I wonder what that is in reference to because Manolis lived in Breij, not Jerusalem). I suspect that Kyrani had been accompanied on her trip from Greece by her other son, Alexis, as a Stamatia A Kassotis, which was the name of his wife, is listed on the wedding certificate as maid of honour. Surely Kyrani was present at the wedding, too. She ended up staying in Breij with the family until her death, and was buried there in the forest. But while she was alive, Manolis instructed her to worship Vitsa daily.

Vitsa was lonely in Breij. Living on a farm was a far cry from her cosmopolitan life in Jerusalem. From a fancy-free girl who had just graduated from school and loved her piano, she became a housewife who knew nothing about keeping home or cooking. With time she evolved into an excellent cook and baker. I wonder if it was the fellahas at Breij that taught her how to make all her Palestinian delicacies: hummus, babaganoush, tabbouleh, maqlubeh, and the like.

A few years later, Manolis bought Vitsa a piano which gave her great joy. In the meantime, the arrival of the couple’s children ensured she’d be plenty busy.

The first arrival was in June 1924: a daughter, named after Manolis’s father: Vassilia, aka Vasso. She was the apple of Manolis’s eye. On her birthday in 1970, he wrote in his diary:

“Today is our Vasso’s birthday and my mind and my thoughts take me back to 1924. She was born through a very difficult labour and the doctor had struggled to save her. Much emotion, prayers and thanks to God who saved mother and daughter. My late mother-in-law was despairing, which caused me much anxiety and fear, but afterwards everything was joyful and happy.”

A year earlier he had written on the same occasion:

“She brought us great love, joy and great happiness at work.”

He couldn’t bear to hear his “Kassotina” cry. No matter where he was or what he was doing on the estate, he’d drop everything and rush home as soon as Vasso’s cries reached him; he would take her in his arms to soothe her—to the frustration of everyone else who tried to adhere to accepted child rearing practices of the time. They needn’t have worried: Aunt Vasso was one of the most resilient and together people I’ve known.

Moving to Jerusalem

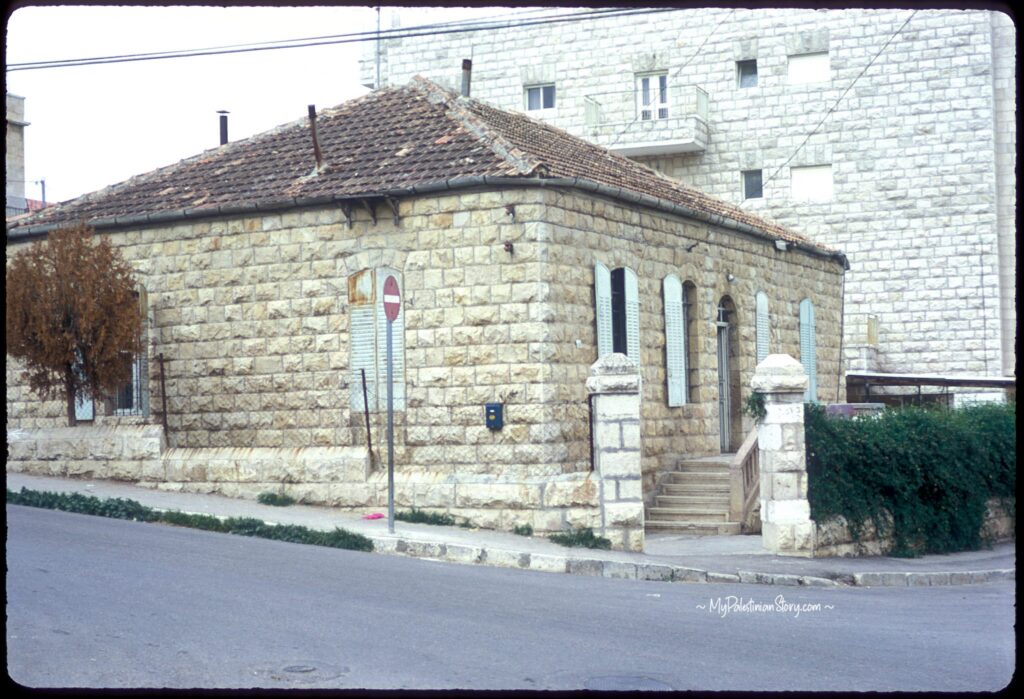

When the time came for Vasso to go to school, she was sent to live with her maternal grandparents in Jerusalem with whom she spent the weekends while during the week she was a boarder at the German Schmidt’s Girls College. Manolis had already anticipated that they’d be needing a base in Jerusalem so in April 1926 he purchased a newly built one-storey stone house in the recently developed quarter of Katamon, close to the Greek Orthodox church of St Simeon. He rented it out and in 1933 had it renovated so the family could move in.

In the meantime, for a short spell they had made a home in the Greek Colony where their second daughter was born in January 1930: my mother Anna. Her earliest memory, at age three, was of her father holding her by the hand as they stood outside the Katamon house and explaining that this would soon be their new home. The last child, Mary, was born in the Katamon house in December 1935. The family was complete.

Breij remained very much in their lives and was a place of which not only the sisters, but other members of the family have very fond memories. Manolis would work there during the week and join the family in Katamon on weekends. The girls were thrilled when during the holidays—Christmas and Easter—Manolis stayed in Katamon longer. During the summer holidays, the family would migrate to Breij where they would host family and friends. (There is much to say about Breij so I will dedicate a separate post to it at a later time.)

Despite spending most of his time in Breij, Manolis was actively involved in the affairs of the Greek community in Jerusalem which, according to some estimates, numbered several thousands. At the beginning of the twentieth century, a club (Λέσχη) was built in the area that came to be known as Greek Colony, thanks to a large part to the Greek Orthodox Patriarchate Treasurer (Σκευοφύλακας) Archimandrite Efthymios who donated the land. In 1938 the “Hellenic Community of Jerusalem” (Ελληνική Κοινότης Ιεροσολύμων) was founded with Themistoklis Saoulis as president. Manolis was a member of the executive committee which also included names that I have been hearing about for most of my life: Tokatlidis, Vareltzis, Philalithis, Ignatiadis, Antippas.

My mother remembers her father in his Jerusalem days as handsome, upright and brave—what in Greek they call levendis (λεβέντης). He’d ride his horse from Breij to Jerusalem at night without fear. Later on he bought a car, a Ford, so he could pick them up from the train station when they went to Breij.

Manolis was a kind and affectionate father but at the same time especially strict, which my mother attributed to his clerical upbringing that influenced his mentality. It’s that mentality that the girls, particularly the eldest, came up against as they became teenagers and wanted to spread their wings. Yiayia, being more “modern”, would intercede on Vasso’s behalf when the latter’s requests to join friends in outings met with Manolis’s stern objections.

A film by Nando Schtakleff – Jerusalem, 1946

The family was generally comfortable but their finances went through many ups and downs. Agriculture is an unreliable source of income with good times and leaner years following each other in unpredictable patterns. The political situation in Palestine also had an impact on Breij’s business. At times of serious troubles, for example, during the Arab Revolt of 1936-1939, or the various terrorist attacks by underground Jewish organisations, Manolis was not always able to make it to Breij, and the family’s finances would suffer as a result. With the outbreak of the Second World War, during which the warring parties temporarily laid their arms down, business was much improved and so did the family’s finances.

Manolis was incredibly generous but not the best money manager. When business at Breij was going well, he would indulge his generosity, for instance, by treating everyone at the Greek Club. Saving money was not on his agenda, much to Vitsa’s dismay who would try to squirrel away as much as she could. Her clandestine thrift stood the family in good stead when their fortunes turned for the worst with the partition of Palestine. ❖

The story of Papou Manolis continues in a second blog post, coming soon.

What an etraordinarily interesting story this is Marina mou, beautifully written. I remember you at a CVAR event when showing a photo of the house in Katamon.

Thank you, Katie. Much appreciated!

You’ve done an amazing job capturing this piece of history and bringing the people of the Greek community in early 20th C Palestine to life. Looking forward to more!

Thanks so much, Kathy!

Wonderful and vivid! Looking forward to the next installment, Marina!

Many thanks, Maia!

At the risk of sounding repetitive, I can’t tell you how grateful I am to read your post. This is not just a post. This is a time capsule; A time machine taking me on a journey everlasting. Your artisanal craft of recounting The lives of loved ones is impeccable and honourable in that Your post honours all those who share this history Especially Honouring your Papou Who I remember as Theo Manolis.Thank you Marina with much love and appreciation your cousin

Thanks so much, Cous’! Means a lot!

Lovely story Marina m

Thanks, Magda!

Enjoyed your article. Thank you for continuing to talk about Palestine and your people who lived in it. It brings back so many memories. I enjoyed seeing that one of your family, like me, went to Notre Dame de Sion. I spent 13 years in the convent between Jerusalem and Strasbourg France.

A very special memory has to do with the Greek Orthodox Church. On palm Sunday my brother and I would go to the church in our Easter clothes holding a palm decorated with flowers, wax eggs and other figurines. We Walked around the church with all the other children. It was one of the highlights of the Easter season. Although I was more or less 5 years old I still smile when I remember.

I am very sorry not to be able to find out if my father did works for the Patriarchate. The odds are good.

Katamon, so many of my family lived there!

Thank you again Marina You are a very special person bring us together with memories

Many thanks for your support, Nadia, and for sharing your own memories!