Preparing to write about the Schtakleffs, my maternal grandmother’s family, the other night I finally had a close look at the photos I took of the “Register“. Its official title is the Register of the Christian Orthodox Community in Holy Jerusalem. Its discovery is one of the big coups of my last trip to my mother’s birth town in the summer of 2015. Before I write about its contents, I figured I’d tell the story of how I got hold of it.

Looking to continue the previous year’s research in Jerusalem into official documents, I started by asking around about burial records and was told that Bajali, a jeweller in the Old City, was responsible for issuing licences for burials at the Greek Cemetery so he would have the records. I mentioned this to George Tsourous (a Greek social anthropologist who had spent more than a year studying the Greek Orthodox community in Jerusalem – mentioned in a previous post) in our first meeting so we decided to go check there.

The man at Bajali’s didn’t speak much English but George spoke Arabic sufficiently well to communicate what we were after. He knew nothing about burial records but his brother Nabil did, only he was away and he’d be returning to town on Saturday. It was only Wednesday so I had a few days to wait.

After a delicious lunch of falafel at Lina’s (best in the world in my book!) George and I decided to check out Gethsemane where there is another Greek Orthodox cemetery. Apparently that’s where the Greek Orthodox were buried in the period 1949-1967, when the Mt Zion cemetery lay on the wrong side of the 1949 armistice line that divided Jerusalem.

We regrouped, and headed out of Lion’s Gate.

Gethsemane

Gethsemane is an olive garden at the foot of the Mount of Olives. The name Gethsemane derives from the Aramaic for olive press. The Church of The Tomb of the Virgin Mary lies at the edge of the garden, only a few minutes’ walk out of the Old City.

It’s been carved out of rock, underground. Over the centuries, the church has been destroyed and rebuilt many times as is the case with many holy shrines. And as is the case with other churches in Jerusalem, mostly notably the Holy Sepulchre, this one, too, is ‘shared’ between different denominations, mainly Greek Orthodox and Armenian (the Greeks go down the right side of the steps and Armenians down the left – Lord have mercy on both of them!) while the Syriacs, the Copts, and the Ethiopians have minor rights. According to Wikipedia, a niche south of the tomb is a mihrab indicating the direction of Mecca, installed when Muslims had joint rights to the church which they no longer do. The sacred is political in this part of the world…

On arrival, we could see a cemetery but the gate was locked. We went down to the church (I making a point of walking right down the middle!) where the Serb priest, representing the Orthodox side, told us that the mother of the priest in charge of the cemetery would be coming to clean at 5pm, so she might be able to open the gate for us.

It was a hot day so we cooled ourselves in this cavernous church, George observing the pious through his ethnographic eyes and I happy to have discovered an inscription above the icon of the Virgin Mary the Jerusalemite referencing Patriarch Damianos I. Good photo op under the name of another ancestor: my maternal grandfather was a nephew of the Patriarch which is how my grandfather found himself in Jerusalem (that story in another post).

“During the Patriarchate of Damianos I”

We still had more time to kill so we walked to the Church of All Nations which is just up the road. When we returned, sure enough the mother of the priest was there. She told us that her son was out of town but would be returning soon. She didn’t think though that there were any graves left: all of them had been moved to the Mt Zion cemetery.

Mission not accomplished. But I still had ten days ahead of me.

The Mukhtar at St James’s

Fortunately George was well connected with the Patriarchate. A few enquiries led us to the chapel of St James, adjacent to the Church of the Resurrection (aka Holy Sepulchre) where we were told we would find the mukhtar of the Arab Greek-Orthodox community (aka Rûm). Let’s explain these terms before moving on.

According again to Wikipedia, “Mukhtar (meaning ‘chosen’ in Arabic: المختار) is the head of a village … in many Arab countries as well as in Turkey and Cyprus. The name is given because mukhtars are usually selected by some consensual or participatory method, often involving an election.” I don’t know if they are elected in Jerusalem but in Cyprus where this relic of Ottoman rule is still in use, the mukhtars, at least today, are appointed, not elected. They are in charge of issuing and/or notarising documents that relate to births, deaths, inheritances and the like, the assumption being that they know all the people in their community and as such they can testify as to their circumstances, eg that Peter and Paul are Mary’s sons. In this day and age, mukhtars don’t really have a clue who we all are but District Offices are saving a ton of money by having them do this work. Mukhtars don’t get paid a salary, they don’t even receive a stipend to cover their expenses (paper, stamps etc). It’s all about the glory of serving the community! At least that’s the situation in Cyprus. But I digress…

As for the Rûm, that’s the term used for Christian Arabs who follow the Greek Orthodox (Eastern) church as a means of disambiguation. Because when you say Arab Greek Orthodox… well, it gets confusing: are we talking about Arabs that are Greek and Orthodox, or half Arab – half Greek or…. ? Rûm derives from the Greek word Romios (Ρωμιός), a later form in Greek of Ῥωμαῖοι Rhomaioi: “Romans”. “It refers to the Byzantine Empire, which was then simply known as the ‘Roman Empire’ and had not yet acquired the designation ‘Byzantine’, an academic term applied only after its dissolution.” (Wikipedia) The reality is that many Arabs will still tell you they’re Greek Orthodox if you ask them about their religion. I suspect the word Rûm is for the more sophisticated amongst them.

Be that as it may, the mukhtar at St James’s, George Kamar*, is who we found ourselves, George and I, talking to about a week later. A likeable older man with bright blue eyes. He was accompanied by another man, slicker, whose role I haven’t figured out. Sure they had records and sure they could look for the Schtakleff name—in fact the mukhtar remembered it—but they’d need a few days and they would write it all down for me. “Actually,” I said, “I would really like to make copies of the register, perhaps by photographing?” “No problem. Come back on Saturday morning.”

I was thrilled to be finally getting somewhere with my search. So the plan for Saturday which would be my last full day in Jerusalem was to go back to St James’s with George at 10am when they opened up and also visit the Greek Orthodox cemetery on Mt Zion one more time and that was only open till noon. And at 12:15 I would be picked up at the bottom of Jaffa gate for a last exploration in West Jerusalem. A bit of a tight schedule but really quite doable.

George texted on Saturday morning that he’d had a late night with a glass too many and needed recovery time. So I set off for St James’s on my own arriving at 10:00 sharp.

It was fairly quiet in the plaza in front of the Holy Sepulchre – quite unlike all my previous visits to the area. The door to St James’s was still locked. I enquired at the Church of the Resurrection and was told they’d open in 10 minutes. Sure enough at 10:15 the mukhtar and his sidekick arrived. I watched them from across the plaza bang on the old door several times to get it open and I immediately followed them in. They received me warmly, the sidekick perhaps a little too warmly, holding me by the elbow in a gesture which had me wondering: Friendly old man or dirty old man? For some reason he really made me uncomfortable. (George would blame it on my tourist uniform of Bermuda shorts and sleeveless top!)

The sidekick got busy preparing the church for the arrival of the faithful while I sat with the mukhtar and chatted. He told me he used to work in the museum that is now the Rockefeller so he’s ‘half an archaeologist’. I felt comfortable with him and was glad he was the one who was keeping me company. I didn’t want to press them but the church prep was taking too long and I was getting antsy so finally I suggested that perhaps I should go up to the cemetery and come back later. The mukhtar said something to the sidekick who came up to me and said, “No, wait, I’ll go get the book right now.” And then, in a Bilbo Baggins transformational moment, he got closer to me and practically shouted at my face, “But you have to pay!” I was gobsmacked. I didn’t anticipate being asked for money but more importantly I was greatly taken aback by the aggressive approach.

It took me a few moment to gather my wits but was even more shocked when the man continued, “300 shekels” (about $85) “It’s secret information and to get it, you have to make a donation to the church.” But seeing how disturbed I was by the whole thing, he then lowered his price and said 200 (about $55). I agreed. I was really put off and it would have felt good to just walk out but I wanted to get my hands on those records so badly!

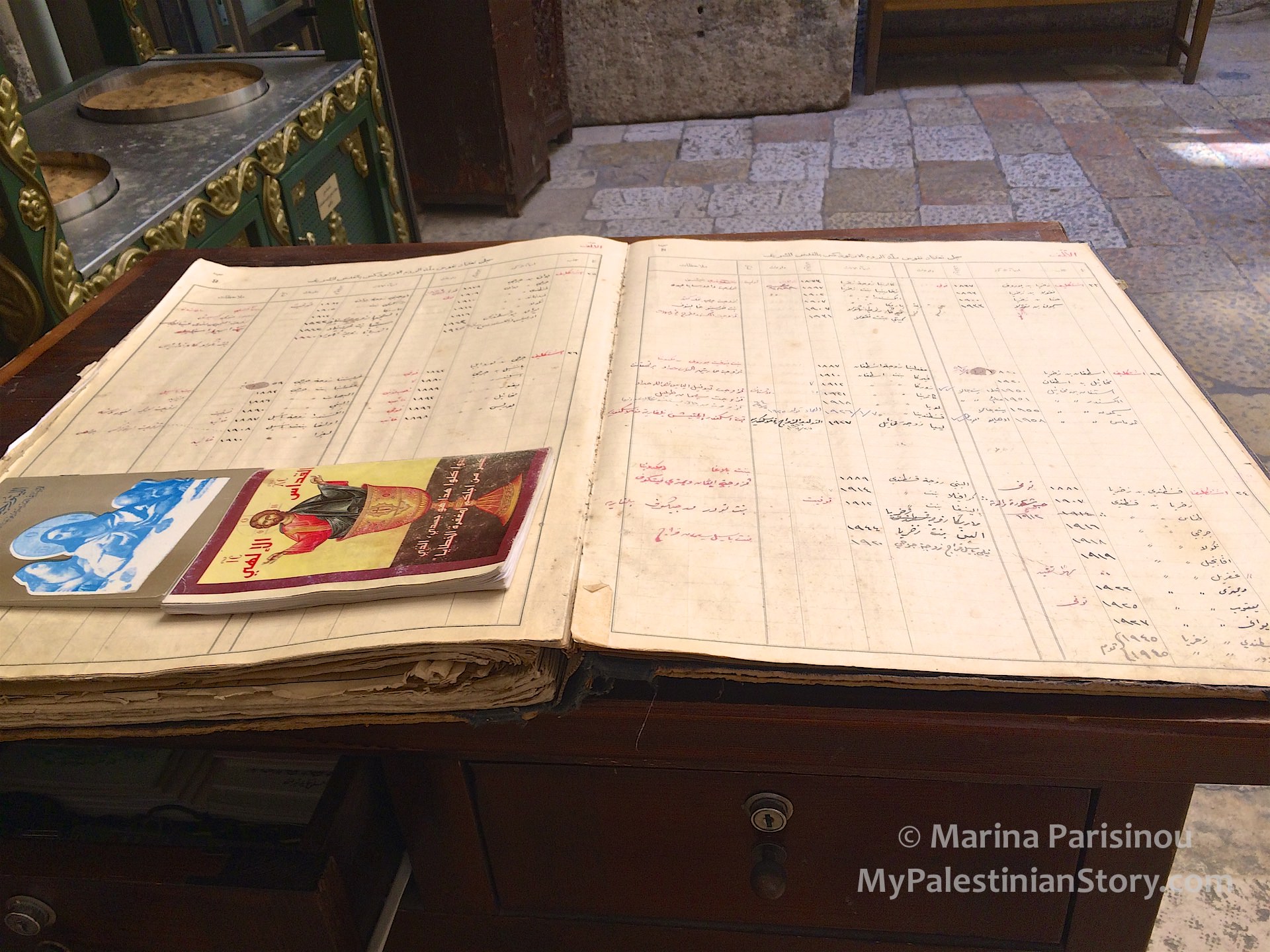

He disappeared for a few minutes and returned with a huge book. There it was, the coveted register, with the best part of two of its big pages listing Schtakleff after Schtakleff after Schtakleff.

My knowledge of Arabic is poor but I can read the script so I quickly located my grandmother’s name amongst so many other familiar ones and my joy overcame the ugly impact of the previous scene.

I made sure to take photographs from different angles and then the mukhtar asked me to go to his office to pay. I was glad to see him issue me a receipt. I would have insisted on it!

I left with mixed feelings. I didn’t mind paying, in fact I would have gladly given a donation had they suggested it nicely. It’s the way it was done that upset me so. But I kept telling myself that it was a donation in memory of my grandmother and that made me feel better.

At The Cemetery

I left, crossed the Muristan and easily found Zion Gate. I was quite gratified to see that I was beginning to get my bearings in this old, muddled town. I exited the Old City and navigated my way to the Greek Orthodox cemetery on Mt Zion.

Munir, the cemetery keeper, was by the door. I had bumped into him earlier in the week, close to the Patriarchate, and was surprised at how much he’d aged since the year before. He now walked with a stick. He’d had a hard time remembering me but when he did he assured me that he had taken care of the grave as I had asked him (and paid him) to do but, you know… trees grow again. I was sure he hadn’t done a thing.

I wasn’t wrong. The grave looked no different from last year, buried under deep foliage, full of dry weeds. I went back to him and asked if he had pruning shears and he handed me a very blunt pair. I returned to the grave and got to work, all the time wishing I had brought my own shears from home and then laughing at the thought of Israeli security discovering them in my luggage. Although it would not have been funny!

It was a hot July day but I was on a mission. Half an hour later the grave was finally clear and could be seen from all sides. I was rewarded with a nice detail on the back that I hadn’t been able to see the previous year. And I left a small hill of weeds and tree branches for Munir to dispose of. (The truth is, although I wasn’t impressed that he hadn’t followed through, seeing him in such poor physical condition, I couldn’t hold it against him.)

By this time I was really running late. I rushed down the steps away from the cemetery and hurried along the exterior of the city walls to Jaffa Gate.

Jerusalem Stone

I was tired and emotionally drained plus sweaty and dirty. I wanted to make it back to the hotel to freshen up and change before my next appointment but only had a few minutes to do that.

Back inside the Old City, as I approached the hotel, a man on the opposite side of the street was seated facing a big fan and holding a tray with ice-cubes in front of it. I couldn’t help laughing and he joined in good-heartedly. “Air condition!” he exclaimed. I asked him if I could take a photo and he happily accepted.

He then asked where I was from so I explained I was from Cyprus but my mother was from there, from Jerusalem. On hearing that, he invited me into his store—to give me a gift. I hesitated as I was pressed for time plus I was mistrustful of his intentions. The morning at St James’ had left a bad taste in my mouth. But he insisted and somehow I couldn’t refuse him so I followed him inside the dark shop. He took a small blue round stone and offered it to me. “It’s Jerusalem stone—from Elat,” he said. He then asked me to wait a moment and he got busy attaching a small silver clasp on it so it could be hung. I braced myself for the price but no, he truly meant it as a gift!

He then took a long look at me and said, “I’m not a psychologist but I saw you coming up the street and I thought to myself, Her body is here but her mind is somewhere else.” I was touched. “I was just up at the cemetery. My mind was there, with my ancestors.” Then he asked about my origins and suggested that I could well have Jewish blood or even Arab (but for some reason insisted on Jewish) “and there’s nothing wrong with it.” I told him that I’d looked into it and we are Greeks and Bulgarians. Finally as he was easing off his insistence I said, “In any case, I think of my mother as Palestinian because that’s how she thinks of herself.” He smiled broadly.

With that small gesture of an unexpected, genuine gift and a few thoughtful words from a stranger, all the bad feelings of the morning were undone. Jerusalem was smiling on me. My heart was filled with peace. ❖

______________________

Edited on 7 Jan 2024:

* Corrected the mukhtar’s surname.

Very interesting article ,brought memories back ,xxx

Thank you, Eleni. Coming from a native, it means a lot!

Beautiful story. I have been reading about your research for some time now. You are doing a great job.

Many thanks, Tasso. So glad you enjoy my research!

Such a beautiful story. I am a Schtakleff myself and my curiosity about my family origin (especially since no one seems to have any answers for me) led me to this great blog.

Thank you, Nadine. Happy to hear from another Schtakleff and would love to connect with your privately and share information.

Yes I would love that. I have mentioned my email address in the reply form. If you have it please email me and i would really appreciate talking privately about this 🙂

I am the son of George Constantine Schtakleff, I live in Raleigh North Carolina. I am the great great grandson of Zacharia who came from Tetovo ( Macedonia). I have the complete Schtakleff family tree. Thank you Marina for the great trip details and following up our family roots. I have also gone further back and met some family members who live in Tetovo

How wonderful to hear from you, Elias! Thank you for getting in touch and the kind words. I would love to exchange family information with you. Will drop you a line via email.

Very nice article… I liked the way you have presented your meeting with the shopkeeper in the old city (it took me back to the Alchemist novel, when the boy received the stones of wisdom, and when he met the crystal’s merchant ).

Anyhow, Thanks for sharing your experience as you have visited our city.

Also, I liked the idea of looking for /exploring the history of your family.

To tell you the truth, I crosscut with your piece as I am stuck in small research about “Mukhtar”, and their responsibilities within the Christian community in Jerusalem.

Thanks for reading, Rami, and for the kind words. Enjoy your Mukhtar project!